Framing: Difference between revisions

No edit summary |

|||

| Line 8: | Line 8: | ||

'''Actually there are 16 circles above.''' | '''Actually there are 16 circles above.''' | ||

== Framing in Politics == | == Use of Framing == | ||

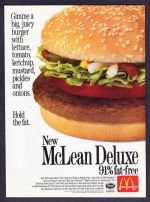

[[File:McLean.jpg|alt=McLean|thumb|202x202px|Contains 9% Fat of 91% Fat Free?]] | |||

Framing has been known as a method for manipulation for a very long time<ref>Propaganda, Edward L Bernays, 1928.</ref>. For instance, Mcdonalds has been using it to sell poor quality food to people for over half a century! | |||

=== Framing in Politics === | |||

[[File:Political framing.jpg|alt=Political framing|thumb|Political framing]] | [[File:Political framing.jpg|alt=Political framing|thumb|Political framing]] | ||

Revision as of 05:33, 23 March 2022

Look at this picture of a rabbit, can you see its long ears...?

...actually it's a duck. If you haven't seen this picture before, the initial comment above will prime you to think it is a rabbit, where in fact it could easily be either a duck or a rabbit. The brain determined to accept the suggested duck option rather than to critically assess what the author suggested as it takes more energy. This is called framing, it occurs when information is hazy and requires energy to discern so you default to mimic a third parties opinion.

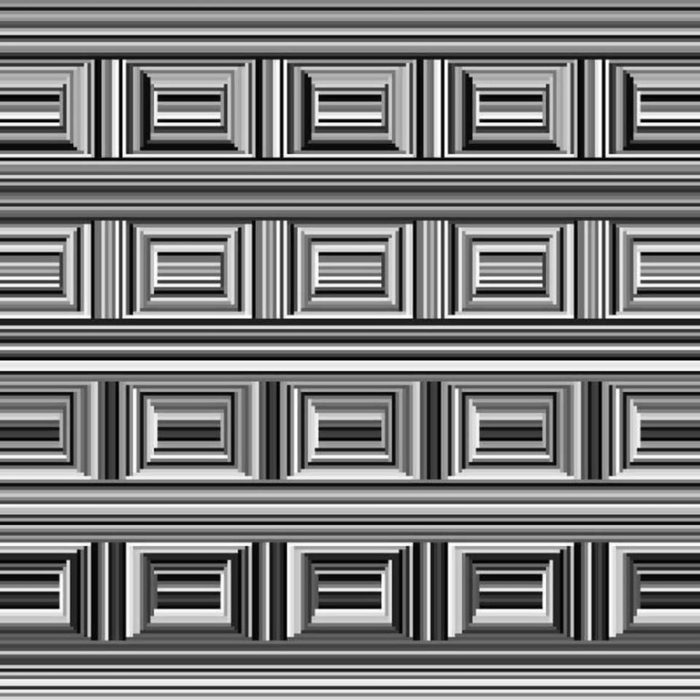

This gives the third party power to control what is presented as fact. Without the priming you might have known that it was both a duck and a rabbit but it was presented by an author (an authority) as only the former. It is the perceived authority of the presenter which enables the efficacy of framing much like the placebo effect. i.e. doctors, in a white coat giving you a medicine has been shown to make the effect of a medicine more potent. Lastly try this image, if a doctor tells you there are 16 rectangles, can you see them?

Actually there are 16 circles above.

Use of Framing

Framing has been known as a method for manipulation for a very long time[1]. For instance, Mcdonalds has been using it to sell poor quality food to people for over half a century!

Framing in Politics

So that's framing, but how does this distort everyday life? Framing involves the social construction of a social phenomenon – by mass media sources, political or social movements, political leaders, or other actors and organizations. Participation in a language community necessarily influences an individual's perception of the meanings attributed to words or phrases. Politically, the language communities of advertising, religion, and mass media are highly contested, whereas framing in less-sharply defended language communities might evolve imperceptibly and organically over cultural time frames, with fewer overt modes of disputation.

Heres an experiment you can do at home. Ask a friend simply, what does the political Left stand for? The ask someone else, you will find that it is difficult to pinpoint precisely exactly what Left and Right stand for they are very generalist terms[2]. The image to the right shows a general breakdown of what this is considered to be in the US, however to concretely state that the Left believes in on policy and the right believes in another is a supposition.

The media have the power and tendency to immediately portray a political point to the public in either of two camps. However, this very method of portrayal, angle of attack can affect the perceptions of the general public which is trying to be objectively informed of the new policy[3]. The unfortunate consequence of this is instead of taking a new idea on the basis of merit by putting it into a specific camp you immediately generate opposition and polarise groups to one another. In reality a political ideal can benefit everyone around the table.

Experimental demonstrations

In a well-known experiment, two groups of people are instructed to analyze the crime figures for a fictional city called Addison[4]. They are then asked to describe what strategy the authorities 10 should adopt to make the city safer. The language used in the instructions is different for each group. Group 1 is told that crime is like a predator lurking in an increasing number of neighborhoods, while Group 2 is told that crime is like a virus infecting an increasing number of neighborhoods. Both groups are then asked to analyze the numerical data and identify the best way to tackle the problem. It turns out that the wording of the assignment affects the respondents’ interpretation of the data. If crime is a predator, the natural response is to hunt it down.

The first group accordingly opts for stronger enforcement. On the other hand, if crime is a virus, the natural response is to attack it at the source. The second group of respondents accordingly believes that efforts should focus on the causes of crime, such as poverty and lack of educational opportunities. One might be inclined to think that this is an obvious outcome given the heavy-handed nature of the metaphors employed. In a follow-up experiment, the instructions therefore refer only once to the predator or the virus, while the rest of the instructions consists of a detailed technical description of the case. In spite of this, the outcome is the same. Language shapes the way in which the respondents perceive the world.

Next – and this is where things really get interesting – the respondents are asked why they had chosen either approach. They all respond that their choice is based solely on the crime figures. The wording of the instructions has thus become the filter through which the respondents perceive the facts, but they are unaware of this. They think that their opinions are based on objective numerical data. This has enormous implications. Politicians who are able to impose their language can make us perceive the world through a specific filter without us even realizing it.

References

- ↑ Propaganda, Edward L Bernays, 1928.

- ↑ https://yougov.co.uk/topics/politics/articles-reports/2019/08/14/left-wing-vs-right-wing-its-complicated

- ↑ Issue framing in online voting advice applications: The effect of left-wing and right-wing headers on reported attitudes https://journals.plos.org/plosone/article?id=10.1371/journal.pone.0212555

- ↑ When Do Natural Language Metaphors Influence Reasoning? A Follow-Up Study to Thibodeau and Boroditsky (2013) https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pmc/articles/PMC4260786/