Framing

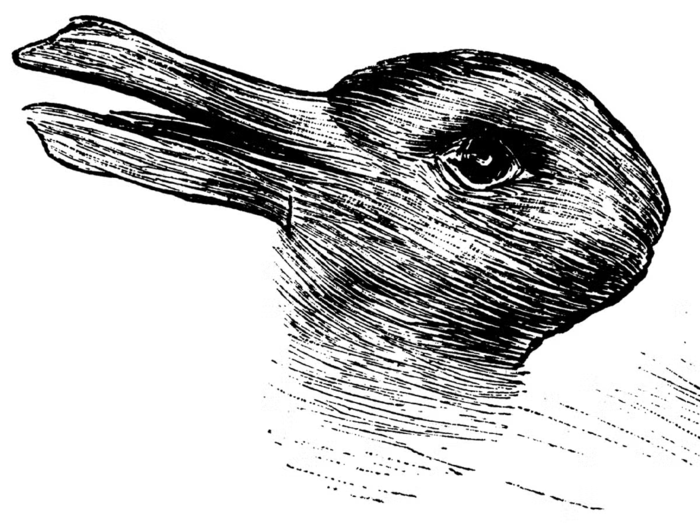

This is a picture of a rabbit looking to the right. Can you see it?

Actually, it's a duck—looking to the left.

If you haven't seen this image before, initially being told it's a duck makes you more likely to see it that way. In reality, the picture is ambiguous, it could be either a duck or a rabbit (see Figure 1).

What's happening here is called framing or optics. Your brain takes the suggested "duck" as a shortcut instead of expending energy to analyze the image critically. When information is unclear, we often rely on external cues—especially from authority figures—rather than thinking deeply ourselves.

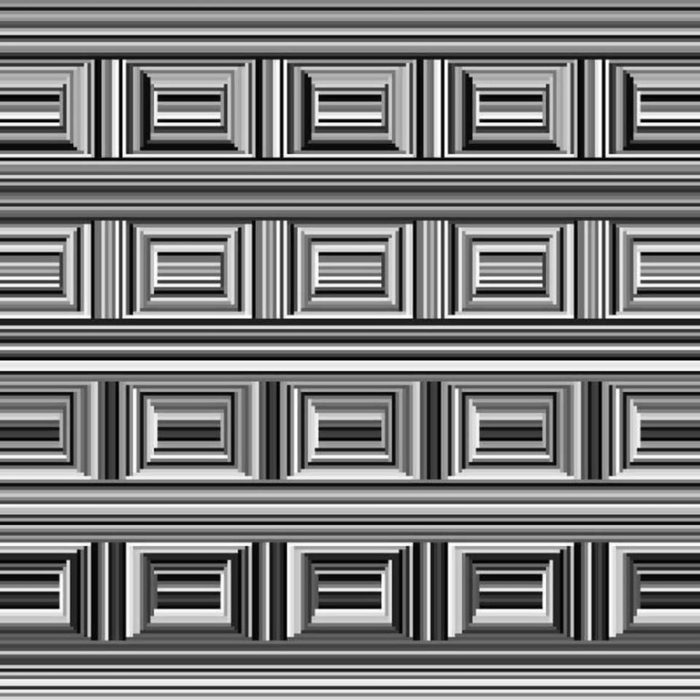

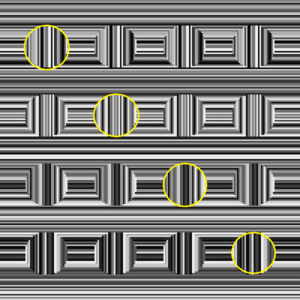

Lastly, try this Coffer, ambiguous figure... There are 16 rectangles, can you see them?

Actually, there are 16 circles above. Have a look at the highlights presented in the image to the right (Figure 2).

Framing occurs when you are given a suggestion that shapes your perception, and your mind accepts it as reality due to availability bias—the tendency to rely on the most immediately available information rather than analyzing alternatives.

Use of Framing

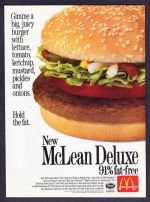

Framing has been known as a method of psychological manipulation for a very long time[1] and is used as the basis of many Dark Patterns. A simple example of this, is this Mcdonalds advert (Figure 3) which emphasises the frame that their new hamburger is 91% fat free, instead of highlighting it contains 9% pure fat!

Pluralism

Framing reveals that there is no singular, fixed interpretation of reality—only perspectives shaped by context, identity, language, and prior experience (see Figure 4). What one person sees as truth may be a distortion or abstraction through another's lens. These differing “truths” are not necessarily in conflict; they are parallel expressions of a deeper, multifaceted reality. Just as a story changes depending on who tells it, the world itself can look entirely different depending on how it is framed. Recognizing that there are multiple valid interpretations of the same event or experience is essential to transcending binary thinking and cultivating a more nuanced, inclusive worldview.

Pivotal Mental States can often act as powerful tools for metacognitive expansion—the ability to think about one’s own thinking. Under their influence, the rigid scaffolding of fixed frames can temporarily dissolve, allowing individuals to step outside their default frames of reference. In this expanded state, people frequently report heightened awareness of the subjectivity of their beliefs, emotions, and perceptions. They begin to see that their personal truth is one among many, and that multiple, even contradictory, perspectives can coexist without invalidating one another. This experience can cultivate a lasting openness—a humility of mind—that helps people embrace complexity, contradiction, and the deep plurality of human experience.

References

- ↑ Propaganda, Edward Bernays, 1928.