The Objectivity Assumption: Difference between revisions

mNo edit summary Tags: Manual revert Visual edit |

mNo edit summary |

||

| (16 intermediate revisions by the same user not shown) | |||

| Line 1: | Line 1: | ||

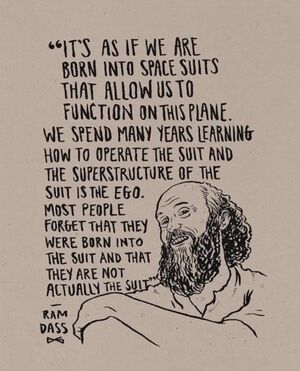

[[File: | ''“The belief that one’s own view of reality is the only reality is the most dangerous of all delusions.”'' - Paul Watzlawick[[File:Ram Dass Objectivity.jpg|alt=Naive Realism|thumb|'''Figure 1'''. Our senses are an abstraction from the world.]] | ||

'''We often | '''We often assume our perceptions are accurate and objective reflections of reality, when in fact they are first [[Framing|framed]], then constructed by our minds.''' Human perception has always been an abstraction rather than a direct replication of the world around us. | ||

[[File:Müller-lyer illusion.jpg|alt=Müller-lyer illusion|thumb|'''Figure 2'''. The Müller-lyer illusion.]] | |||

This abstraction arises from the fact that we perceive the world through a unique lens. Our brains do not simply record external reality—they interpret and reconstruct it by filtering sensory input through layers of memory, context, and expectation. For example, consider optical illusions like the Müller-Lyer illusion (see '''Figure 2'''), where two lines of equal length appear unequal due to the angles of the arrows at their ends. Though the physical stimuli are identical, our visual system frames the image in a way that leads to a distorted perception. This demonstrates that what we “see” is not a direct imprint of reality, but a mental interpretation shaped by the brain’s assumptions about the world. Vision, like all perception, is an act of internal construction. | |||

This assumption of objectivity alongside declining [[neuroplasticity]] is an evolved trait that serves our survival by allowing us to navigate our environment without constant questioning. However, in today’s information age—our modern savanna—recognizing our inherent perceptual [[Cognitive Biases|biases]] is essential for navigating this new world. While our perceptions are subjective, this does not mean that all perceptions are equally valid or that objective truth is absent. Rather, it highlights the importance of confronting our [[cognitive dissonance]] and actively challenging our [[cognitive biases]] to achieve a more accurate understanding of the world. | |||

Latest revision as of 00:24, 9 May 2025

“The belief that one’s own view of reality is the only reality is the most dangerous of all delusions.” - Paul Watzlawick

We often assume our perceptions are accurate and objective reflections of reality, when in fact they are first framed, then constructed by our minds. Human perception has always been an abstraction rather than a direct replication of the world around us.

This abstraction arises from the fact that we perceive the world through a unique lens. Our brains do not simply record external reality—they interpret and reconstruct it by filtering sensory input through layers of memory, context, and expectation. For example, consider optical illusions like the Müller-Lyer illusion (see Figure 2), where two lines of equal length appear unequal due to the angles of the arrows at their ends. Though the physical stimuli are identical, our visual system frames the image in a way that leads to a distorted perception. This demonstrates that what we “see” is not a direct imprint of reality, but a mental interpretation shaped by the brain’s assumptions about the world. Vision, like all perception, is an act of internal construction.

This assumption of objectivity alongside declining neuroplasticity is an evolved trait that serves our survival by allowing us to navigate our environment without constant questioning. However, in today’s information age—our modern savanna—recognizing our inherent perceptual biases is essential for navigating this new world. While our perceptions are subjective, this does not mean that all perceptions are equally valid or that objective truth is absent. Rather, it highlights the importance of confronting our cognitive dissonance and actively challenging our cognitive biases to achieve a more accurate understanding of the world.