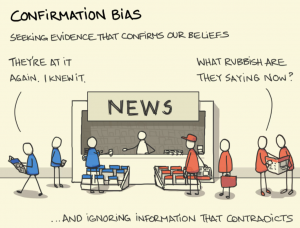

Confirmation Bias

Confirmation bias is the tendency to search for, interpret, favor, and recall information in a way that confirms or supports one's prior beliefs or values[1]. This bias often works within a negative feedback loop with the authority bias.

The bias leads us to live in a world of our own choosing, finding the information that already fits with our beliefs and ignoring or discounting what doesn't. It's the bias that makes two sides get further apart rather than closer together (polarization).

A great metaphor for this is to think of channels of water. As water runs through the channels the channels get deeper, and as they get deeper it pulls more of the water into the main channels until there is only one way. Confirmation bias can act like that.

It's important to work to understand different opinions, not discount them upfront. To use our empathy to understand why others feel the way they do. And when we deliberately seek out information that challenges our point of view we will usually find a richer, more nuanced world that helps build bridges with others rather than drive us apart. A useful tool that enables many to better see these types of biases within themselves are the inducement of pivotal mental states.

Authority Bias

Research suggests that greater authority is given to financial advisors who confirm one’s existing opinions, implying that authority bias is strengthened when it coincides with confirmation bias[2].

The Diderot Effect

This is an effect where we surround ourselves with information the confirms preexisting beliefs. The Diderot Effect takes this into the physical realm, we generally surround ourselves with objects that fit our current sense of identity.

References

- ↑ https://pages.ucsd.edu/~mckenzie/nickersonConfirmationBias.pdf

- ↑ "Evaluating experts may serve psychological needs: Self-esteem, bias blind spot, and processing fluency explain confirmation effect in assessing financial advisors' authority". Zaleskiewicz, Tomasz; Gasiorowska, Agata (2020). Journal of Experimental Psychology: Applied. 27 (1): 27–45. doi:10.1037/xap0000308. PMID 32597675.