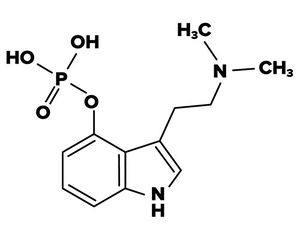

Psilocybin

The active psychedelic ingredient (when converted to psilocin) found within magic mushrooms. Psilocybin has been found to be effective therapy for treatment resistant depression (TRD).

Psilocybin (Figure 1) degrades quickly into its active metabolite psilocin after ingestion. Both psilocin and psilocybin exhibit affinity for a range of serotonin receptors (5-HT1A/B/D/E, 2B, 5, 6, 7) with high affinity for the 5-HT2A receptor.

History

A chemical found in more than 100 mushroom species and used for millennia in Indigenous communities in Mexico and Central America as part of celebrations, healing rituals, and religious ceremonies. Investigated by psychiatrists in the 1950s and 1960s before the 1971 Controlled Substances Act designated it a Schedule I drug.

Effects During the Psychedelic Experience

It takes 20-40 minuets for Psilocybin / Psilocin to have an psychological effect after ingestion. The peak of this effect occurs within 60-90 minutes which then subsides substantially (by over 50%) within 180 minutes (see Figure 2), the entire session can last between 2–6 h[1].

The most common short term effects include:

- Altered Perception of Time and Space

- Visual Hallucinations and Changes in Visual Perception

- Emotional Changes

- Altered Thought Processes

- Physical Sensations

- Changes in Motor Skills and Coordination

- Altered Sense of Self: often referred to as "ego dissolution."

Compared to amphetamines, which increase the firing of neurons in more typical, synchronized patterns, psilocybin disrupts brain activity both locally and regionally, leading to a desynchronization of neurons that usually fire together.[2]

Whether these effects are experienced is dependent on dosage (see Figure 3), which at its lowest perceptual dose is around 10µg.

Long Term Effects

Many long term effects are thought to be caused by neuroplasticity, these include:

- Reduced depression and anxiety: Psilocybin-assisted therapy is being investigated for its potential to treat depression and anxiety disorders. Some studies have shown promising results, with long-term reductions in symptoms observed in patients.

- Improved mood and well-being: Psilocybin has been shown to have positive effects on mood and well-being, with some users reporting feeling more connected to themselves, nature, and others after their experiences.

- Increased openness to experience: Studies have shown that psilocybin can lead to a lasting increase in openness to experience, also known as the "Big Five" personality trait. This can manifest as greater curiosity, creativity, and appreciation for beauty and diversity.

- Enhanced self-awareness and spirituality: Psilocybin can trigger profound introspective experiences that lead to increased self-awareness and spiritual insights. This can be a valuable tool for personal growth and development.

Depression Dosage

Best practice indicates that a body weight derived dosage of psilocybin of 0.3mg / kg or 25mg should be used[3]. In the realm of magic mushrooms this is approximately 2.5 grams of dried Psilocybe cubensis. This dose is given as follows:

1. Recruitment and medical screening. Tapering of other medicines if needed.

2. Prep sessions 1 and 2 spaced over 2 weeks.

3. Day 0: 1st Psilocybin 25mg dose.

4. Day 1: 90 minute integration session.

5. Day 8: 2nd Psilocybin 25mg dose.

6. Day 9: 90 minute integration session.

These standard doses has been found to have substantially better clinical outcomes than lower doses such 10mg or microdosing[4] (see Figure 4). This equates to 10–20µg l–1 psilocin in plasma, which corresponds to ~60% occupancy of serotonin 2A (5-HT2A) receptors in the neocortex of humans.[1]

A heroic dose, which is usually reserved for experienced psychedelic users is considered to be at the upper end of the dosage spectrum — typically around or more than 5 grams of dried psilocybin mushrooms or anywhere from 25 to 40 mg of pure psilocybin.

Psychedelic Experience

During clinical studies it is common for those carrying out the trial to match the dynamic of the psychedelic experience (trip) with a musical playlist which includes:

- Low Vocalization (for the onset) - commonly classical, low volume (first 45 minutes).

- Peak Emotion - percussion, higher volumes (45-90 minutes).

- Comedown - Can be choral, melodic, commonly have female voices, nature sounds or mimics the "outside world" (after 90 mins).

Combination Therapy

By combining psilocybin with other compounds it is theoretically possible to decrease adverse effects whilst maintaining or increasing desired effects. Below is a list of medicines thought to compliment psilocybin therapy:

- Niacin - in combination with psilocybin is termed the Stamets Stack.

- MDMA - in combination with psilocybin is termed a hippie flip.

Interactions

To some degree psilocybin interacts with the following medicines: buspirone, chlorpromazine, haloperidol, risperidone, ketanserin, ergotamine, escitalopram and alcohol[5].

Reference

- ↑ 1.0 1.1 Psychedelic effects of psilocybin correlate with serotonin 2A receptor occupancy and plasma psilocin levels. MK Madsen Neuropsychopharmacology, first published 2019. Accessed on 5th November 2022 via https://www.nature.com/articles/s41386-019-0324-9

- ↑ Siegel, J. S., et al. (2024). "Psilocybin desynchronizes the human brain." Nature 632(8023): 131-138.

- ↑ Pharmacokinetics of escalating doses of oral psilocybin in healthy adults. Brown RT, Nicholas CR, Cozzi NV, Gassman MC, Cooper KM, Muller D, et al. Clin Pharmacokinet. (2017) 56:1543–54.

- ↑ Single-Dose Psilocybin for a Treatment-Resistant Episode of Major Depression. Guy M. Goodwin. First published November 3, 2022. N Engl J Med 2022; 387:1637-1648. DOI: 10.1056/NEJMoa2206443. Accessed on 5th November via https://www.nejm.org/doi/full/10.1056/NEJMoa2206443

- ↑ Drug–drug interactions involving classic psychedelics: A systematic review. Andreas Halman , Geraldine Kong, Jerome Sarris and Daniel Perkins. Journal of Psychopharmacology 1–16 2023. https://journals.sagepub.com/doi/pdf/10.1177/02698811231211219