Magic mushrooms

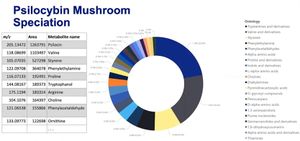

The term Magic Mushroom often refer to medicinal mushrooms. More often than not the term specifically references psilocybin mushrooms which have been used as entheogens for spiritual, religious, and divinatory purposes around the world. Whilst these mushrooms are renowned for containing the psychedelic chemical psilocybin (a tryptamine) like all phytomedicines they also contain an array of parts of psilocybin and other related psychedelic compounds including phenylethylamines[1] (See Figure 1). Their legality varies across the globe.

History

Based on depictions in rock drawings, some historians speculate that magic mushrooms may have been utilised as early as 9000 B.C. by primitive societies in North Africa (see Figure 2). More concisely they have been portrayed in the Pre-Columbian sculptures and glyphs found throughout North, Central, and South America and may also be observed in Stone Age rock art in Africa and Europe.

Species

Magic mushrooms include the biological genera Copelandia, Gymnopilus, Inocybe, Panaeolus, Pholiotina, Pluteus, and Psilocybe.

Psilocybin

There are hundreds of species of psilocybin mushrooms but Psilocybe cubensis is the most common mushroom used for inducing psychedelic experiences due to its ease of cultivation. In the wild, it is commonly found on cow dung but can also be found on horse and buffalo dung.

Magic Mushroom Potency

Cubensis is reported to be “moderately potent,” with analytical reports ranging from 0.7 to 13.3 mg per gram (mg/g) of dried mushroom. Bigwood and Beug[2] found “that the level of psilocybin and psilocin varies by over a factor of four among various cultures of Psilocybe cubensis grown under rigidly controlled conditions, while specimens from outside sources varied tenfold.”

- For the data nerds, the ranges for individual reports were 0.7-6.2 mg/g[2]; 3.2-13.3 mg/g[3]; 11.5 ± 2 mg/g[4]; 0.7-3.5 mg/g[5]; 6.2-15.1 mg/g[6]; 5 mg/g, 6.3 mg/g, 1.5 mg/g and 1.5 mg/g[7].

Psilocybe cyanescens (“wavy cap”), Psilocybe serbica, and Psilocybe azurescens are some of the more potent species with regular reports of psilocybin concentrations of over 15 mg per gram and up to 17.8 mg/g![8]

Psilocybe subaeruginosa is a species of moderate-to-high potency found in Australia and New Zealand that has been reported to have from 4.5 to 11.2 mg of psilocybin per gram of dried mushroom.[8]

- Note: these values are for dried mushrooms which are the most common way they are consumed. Mushrooms have reliably been reported to contain about 90% water.

Potency and Storage

A common concentration of freshly homogenized P. cubensis mushroom powder is:

- 0.01 wt.% norbaeocystin

- <0.01 wt.% aeruginascin

- 0.07 wt.% baeocystin

- 1.51 wt.% psilocybin

- 0.04 wt.% psilocin.

In storage, overtime, the most pronounced changes in the decay in concentration over time were observed with psilocybin, which is the main tryptamine alkaloid in fruiting bodies.[9]

After 1 week - The concentration of psilocybin reduced from 1.51 wt.% to 1.31 wt.%. The greatest loss of psilocybin was found in a sample stored in the light at 20°C, where the psilocybin value dropped to 0.96 wt.%. This trend was also observed for norbaeocystin, aeruginascin, baeocystin, and psilocin, where the measured concentration gradually decreased. It is apparent that tryptamines are not very stable in the homogenized mushroom powder.

After 1 month - The degradation to approximately 50 % of the initial concentration of all tryptamines occurred on storage under all of the test conditions. The most significant decrease in concentration to 0.72 wt.% appeared in the sample that was stored in the light at 20°C. This effect is probably due to the photooxidation of alkaloids. The lowest concentration reduction to 0.85 wt.% was found in the dark at 20°C.

After 2 months - This phenomenon was also observed when the most significant degradation to 0.67 wt.% was measured in a sample that was stored in the light at 20°C. In contrast, the smallest loss of psilocybin occurred when the sample was stored in the dark at 20°C, where the psilocybin was 0.82 wt.%.

After 15 months - A very similar concentration of all tryptamines was found after 15 months under all of the storage conditions. The psilocybin concentration varied by a maximum of 0.04 % in these samples. The lowest degradation of psilocybin was found in a sample that was stored in the dark at 20°C. The concentration of all analytes gradually decreased, which corresponds to studies that claim the same but do not state under what conditions.

For the minor alkaloids (aeruginascin, baeocystin, norbaeocystin, and psilocin) the changes in concentrations were negligible after the first week. After one month of storage, a slight decrease in the concentration of all of the remaining alkaloids was seen at a similar time under all of the defined conditions. After two months of storage, all of the alkaloids were reduced, except for psilocin, which decomposed more only in the light at 20°C. After 15 months of storage, no further changes occurred, except for psilocin, whose concentration This article is protected by copyright. All rights reserved. increased (probably due to the degradation of psilocybin).

Dose

Depending on the strain and storage condition (as above) the most common dose is between 1 and 2 grams of dried mushrooms. In regards to psilocybin dosages, in general a therapeutic dose is considered 25mg which is equivalent to 2.5 grams of dried mushrooms. Popularised by the ethnobotanist Terence McKenna a “heroic dose” A is gram or more and are strong enough to take you out of your present reality.

References

- ↑ Presence of phenylethylamine in hallucinogenic Psilocybe mushroom: possible role in adverse reactions. O Beck , A Helander, C Karlson-Stiber, N Stephansson. DOI: 10.1093/jat/22.1.45. Accessed on 18 Jan 2023 via https://pubmed.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/9491968/

- ↑ 2.0 2.1 https://www.sciencedirect.com/science/article/abs/pii/0378874182900149?via%3Dihub

- ↑ https://www.sciencedirect.com/science/article/abs/pii/0378874182900149?via%3Dihub

- ↑ https://www.sciencedirect.com/science/article/abs/pii/S0379073809004927

- ↑ https://www.mdpi.com/1422-0067/23/22/14068

- ↑ https://analyticalsciencejournals.onlinelibrary.wiley.com/doi/10.1002/dta.2950

- ↑ https://onlinelibrary.wiley.com/doi/10.1111/j.1556-4029.2005.00033.x

- ↑ 8.0 8.1 Stamets 1996 Psilocybin Mushrooms of the World: An Identification Guide

- ↑ Stability of psilocybin and its four analogs in the biomass of the psychotropic mushroom Psilocybe cubensis. Gotvaldová, K., Hájková, K., Borovička, J., Jurok, R., Cihlářová, P., & Kuchař, M. (2020). Drug Testing and Analysis, 13(2), 439–446. doi:10.1002/dta.2950