Logical fallacies

Below is a list of simple logical fallacies in regards to the ecological crisis.

Even though confronted with rational arguments humans often persist in holding on to irrational thoughts as confronting long held beliefs causes cognitive dissonance.

"We will innovate out of the crisis."

This is called the ecomodernist argument it has been around for centuries. Think about it this way... Imagine you decided to start smoking, a pack a day, maybe two. I might say but that's bad! It will kill you! then you *shrug* and say medicine will find a cure, just as it always has.

“It's too late, I won’t make a difference.”

This is termed the singularity argument. A counter argument to which is: What’s the alternative? Sitting on the sidelines, while others right this collective wrong? That’s not fair on us. The "don't bother keep consuming" narrative is a contagious and profitable message that continually tries to demoralize and demotivate any and all momentum and benefits a very select few.

“It’s the government’s problem.”

Climate change is a catastrophic failure by governments. But we are voters, and governments act on our behalf. Many of us are drivers, flyers, meat-eaters. Morally speaking, we can share responsibility for harms we are part of or those we fail to prevent between us. I’m not saying you (or I) should feel guilty about this unfolding global disaster, but we should feel ashamed. We should act.

"Capitalism has brought a massive increase in the standard of living for all, how can you argue against it?"

There is no doubt that capitalism has brought incredible stuff but it has brought us thus far. We now know that infinite growth in a closed system won't work.

“It’s too expensive!”

This is the so-called economic argument against mitigating climate change: that it’s cheaper to adjust to a hotter planet. Even if this were factually unassailable (spoiler alert: it’s not), it would be morally flawed. It relies on what philosophers call utilitarianism – the view that we should maximise overall welfare (often, in practice, overall money) even if some people suffer desperately along the way. That’s in direct contradiction to the most basic intuition of common sense morality. It disregards human rights.

Even if we swallowed this pill, it takes another questionable assumption to make the anti-mitigation sums add up. These economic arguments, says the philosopher Simon Caney, assume that future people’s pain, even their deaths, count for less in the cost-benefit calculations if these are further in the future. That isn’t standard economic discounting; it’s discounting the lives of our descendants.

“I’m already vegan and don’t fly.”

This one is the flipside to “it’s all the government’s fault”: putting it all on individuals. That’s inefficient, unfair, and doesn’t work anyway. Going car-free is harder without a good public transport system; leaving mitigation to individuals means putting all the burden on those who happen to make the effort. And individual carbon-cutting, although important, isn’t enough. It won’t avert this catastrophe without governments on board or fossil fuel giants being held accountable. Faced with institutional failure, we shouldn’t feel powerless, but we should all be climate activists, using our own actions to bring about change from above.

“Lying in front of lorries isn’t my thing.”

So don’t do that! But perhaps look past the optics that make you uncomfortable and ask yourself why anyone would feel desperate enough to glue themselves to a road. It’s not because they enjoy it. Then ask what it is that you will do. Write to your MP? Wave banners outside parliament? Demand that your bank or pension fund divest from fossil fuels? Donate to climate justice NGOs? Progress takes a combination of tactics, from lobbying politicians to civil disobedience. Do what you’re good at, as part of a bigger picture.

“I’ve got enough to do already!”

Climate justice isn’t some esoteric goal. It’s about living in a way that doesn’t kill people: doesn’t drown them, burn their homes or give them malaria. So how much money or time or emotional effort should each of us put in for this basic collective morality? I don’t have a final answer because the ethical debate is continuing. But I have an answer that will do for now, for those living comfortably in rich countries. However much we should do to avert this tragedy, it’s more than most of us do now.

China is responsible for this mess not us!

Further reading

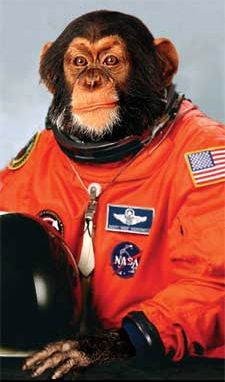

- The chimp paradox: Peters, P. S. (2012). Vermilion. ISBN: 978-0091935580