Cognitive biases

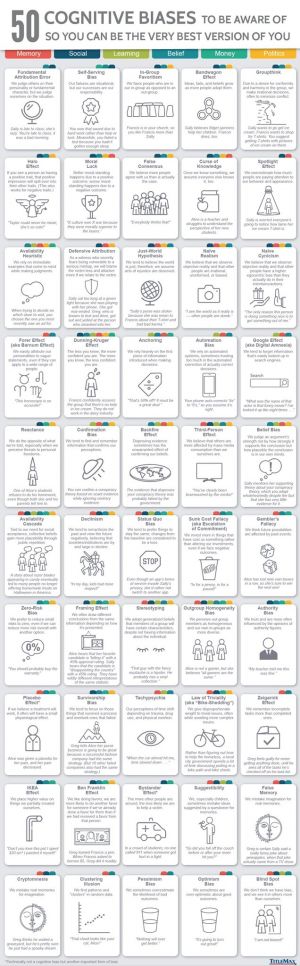

A cognitive bias is a systematic error in thinking that occurs when people are processing and interpreting information in the world around them. They are predictable patterns of thought and behaviour leading to incorrect conclusions.

There are many cognitive biases which have been documented they persist in society as they are self-reinforced by the Dunning Kruger effect combining with the Confirmation Bias, which get worse in crowds[1]. Below is a list of the most prevalent in society ranked on their importance:

- Optimism bias - a computer cannot tell you whether it will rain or not, only the probability of it occurring.

- Additive Bias

- Availability Heuristic[2] - people tend to use the ease with which they can think of examples when making decisions.

- Anchoring Effect - the common human tendency to rely too heavily on the first piece of information offered (the “anchor”) when making decisions.

- Hindsight Bias - the tendency to think that an event was more obvious or predictable than it really was.

- Sunk Cost Fallacy - whereby a person is reluctant to abandon a strategy or course of action because they have invested heavily in it, even when it is clear that abandonment would be more beneficial.

- Halo Effect - people assume a person or thing is good in every way because of one good characteristic.

- Scarcity effect - makes people more likely to buy something when they think it’s about to run out or be taken away from them.

Thought paradoxes

Thought paradoxes are cognitive processes marked by contradiction of typical logical processes. There are many, below we have listed a few.

Allais’ Paradox

Imagine you have to participate in two lotteries, Lottery 1 and Lottery 2. In each lottery, you have two choices. Here are the choices for Lottery 1:

- Option A: Win $1,000,000 for certain (100% probability)

- Option A*: A 10% chance of winning $5,000,000, an 89% chance of winning $1,000,000, and a 1% chance of winning nothing.

Which option would you choose?

Now let’s go to Lottery 2:

- Option B: A 11% chance of winning $1,000,000 and an 89% chance of winning nothing.

- Option B*: A 10% chance of winning $5,000,000 and a 90% chance of winning nothing.

Which option would you choose?

From a probabilistic viewpoint, if you choose option A you should also have chosen option B and if you have chosen option A* you should have chosen option B* because these two options are identical, at least in relation to options A and B. Before your head explodes, suffice it to say that a rational investor would have chosen either options A and B or options A* and B*, but not A and B* or A* and B.

Yet, a large minority of people will choose option A (the safe gain) and option B*. The reason is that when compared to option B, option B* seems like you got roughly the same odds of winning, but if you win you win five times as much as in option B. So option B* looks more interesting. Meanwhile, in the first lottery, the chance of winning nothing is a mere 1%, yet even such a little chance of missing out on a certain gain of $1,000,000 is enough to tempt people to forego the chance of winning $5,000,000 and take the safe $1,000,000.

Obviously, investors make similar bets all the time in financial markets. Option A is essentially a bond investment, while option A* is a typical stock market investment. Option B is an income stock with steady dividends while option B* is a growth stock with no dividends but a bright future.

References

- ↑ Fisher M, Oppenheimer DM. Harder Than You Think: How Outside Assistance Leads to Overconfidence. Psychological Science. 2021;32(4):598-610. doi:10.1177/0956797620975779

- ↑ https://www.goodreads.com/book/show/11468377-thinking-fast-and-slow