Sunk Cost Fallacy

The sunk cost fallacy is when someone continues doing something because of the effort they already put in it, regardless of whether the additional costs outweigh the potential benefits. "Sunk cost" is an economic term for any past expenses that can no longer be recovered.

A simple example...

Imagine that after watching the first six episodes of a TV show, you decide the show isn't for you. Those six episodes are your "sunk cost." A sunk cost fallacy would be deciding to finish watching anyway because you've already invested roughly six hours of your life in it.

A famous example..

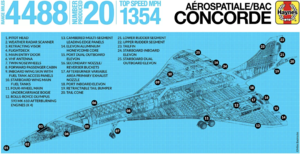

The Concorde (Figure 1) was a supersonic passenger airliner developed in the 1960's and 70's by British and French aviation companies. The project was launched with great excitement, as the Concorde promised to revolutionize air travel by making it possible to fly faster than the speed of sound. However, as the project progressed, it became clear that the costs of developing and operating the Concorde were much higher than anticipated. Despite these challenges, the project continued to move forward, and the Concorde was eventually built and put into service in 1976. This is a prime example of the sunk cost fallacy.

The sunk cost fallacy is a cognitive bias that causes people to make decisions based on the amount of resources they have already invested in a project or activity, rather than on the potential benefits or risks of continuing with it. In other words, people tend to believe that if they have invested a lot of time, money, or effort in something, they should continue to invest in it, even if the costs and risks outweigh the potential benefits.

In the case of the Concorde, the sunk cost fallacy was evident from the beginning of the project. The development of the Concorde was a massive undertaking that required the investment of huge amounts of money, time, and resources. However, as the project progressed, it became clear that the costs were much higher than anticipated, and the economic viability of the project was in doubt.

Despite these challenges, the British and French governments continued to invest in the project, as they believed that the prestige and technological advancements associated with the Concorde would be worth the costs. The sunk costs of the project were already substantial, and it was difficult for the governments to abandon the project without admitting that they had made a mistake. It took a Concorde crash that killed 100 passengers and the aviation crisis after September 11 attacks for them to retire it in 2003.

(I)rrationale

British & French governments thought that they had already invested a lot in Concorde, so they continued pouring even more money and time to make it work. They could have stopped the losses while they were small, but the sunk cost kept them going, which ended up with a much bigger failure. Rational decision-making requires the evaluation of possible future gains and losses. The invested effort, money, or time has no rational impact, but only emotional. So when making decisions, detach your emotions about the sunk cost. It’s unrecoverable. Assess the situation rationally and don’t be scared to cut the losses if you have a better option for investing your resources.

When you find yourself in a hole, the best thing you can do is stop digging.

Questions you can ask to identify this bias...

Do you currently work on a project that you only do so because you have already spent the money rather than because there may be future benefits?

Have you ever increased your investment after initially experiencing a loss?

Do you have someone in your life who you only keep because you have a lengthy history with them?