CO2: Difference between revisions

mNo edit summary |

mNo edit summary |

||

| (20 intermediate revisions by the same user not shown) | |||

| Line 4: | Line 4: | ||

*<p>agricultural emissions (soil nitrous oxide, animal methane)</p> | *<p>agricultural emissions (soil nitrous oxide, animal methane)</p> | ||

*<p>[https://www.iea.org/reports/methane-tracker">methane industrial and permafrost leaks], etc.</p> | *<p>[https://www.iea.org/reports/methane-tracker">methane industrial and permafrost leaks], etc.</p> | ||

*<p>You can explore the [http://energyliteracy.com/ full range here].</p><p>Some sectors have clear paths to reduce emissions electric [https://www.iea.org/reports/global-ev-outlook-2019 vehicles], solar/wind/nuclear, some will be [https://techcrunch.com/2019/02/15/how-to-decarbonize-america-and-the-world slower or more complex to decarbonize]:</p> | *<p>You can explore the [http://energyliteracy.com/ full range here].</p><p></p><p>Some sectors have clear paths to reduce emissions: electric [https://www.iea.org/reports/global-ev-outlook-2019 vehicles], solar/wind/nuclear, however some will be [https://techcrunch.com/2019/02/15/how-to-decarbonize-america-and-the-world slower or more complex to decarbonize]:</p><p></p> | ||

*<p>[https://www.iea.org/reports/tracking-transport-2019/aviation air travel]</p> | *<p>[https://www.iea.org/reports/tracking-transport-2019/aviation air travel]</p> | ||

*<p>[https://www.iea.org/reports/tracking-industry-2019 industrial emissions]</p> | *<p>[https://www.iea.org/reports/tracking-industry-2019 industrial emissions]</p> | ||

*<p>Some agricultural emissions, methane.</p> | *<p>Some agricultural emissions, methane.</p> | ||

[[File:A ton of CO2.jpg|alt=A ton of CO2 | [[File:A ton of CO2.jpg|alt=A ton of CO2|thumb|'''Figure 1'''. A ton of CO2]] | ||

<p><b>To keep below two degrees, we will need to dramatically reduce current emissions and simultaneously remove 10-15 gigatons of CO<sub>2</sub>/yr from the atmosphere by 2050 and scale that to about 20+ gigatons annually by 2100. Depending on how quickly we reduce emissions, the amount we need to remove from the atmosphere scales proportionally.</b></p><p>Greenhouse gas emissions are described in units of tons. It’s hard to think about how much “a ton of gas” really is -- this is how big, at surface temperature and pressure. Here’s an animated video visualizing a bunch of these one-ton balls in New York City.</p | <p><b>Recent data shows progress is too slow. To keep below two degrees, we will need to dramatically reduce current emissions and simultaneously remove 10-15 gigatons of CO<sub>2</sub>/yr from the atmosphere by 2050 and scale that to about 20+ gigatons annually by 2100. Depending on how quickly we reduce emissions, the amount we need to remove from the atmosphere scales proportionally.</b></p><p>Greenhouse gas emissions are described in units of tons. It’s hard to think about how much “a ton of gas” really is -- this is how big, at surface temperature and pressure. Here’s an animated video visualizing a bunch of these one-ton balls in New York City.</p> | ||

< | <HTML><iframe width="100%" height="315" src="https://www.youtube.com/embed/DtqSIplGXOA" title="YouTube video player" frameborder="0" allow="accelerometer; autoplay; clipboard-write; encrypted-media; gyroscope; picture-in-picture" allowfullscreen></iframe></HTML> | ||

< | <p>You may also hear people talk about “''400 parts per million CO<sub>2</sub>''” or similar. This maps directly to the amount of gas emitted: when emissions mix into the atmosphere, we reference concentrations of the emitted gas as a portion of the atmosphere. This is like stirring sugar into a cup of coffee. For every million parts atmosphere there are 400 parts ''CO<sub>2</sub>'' this proportion has been rising steadily exactly since the industrial revolution...</p><p> | ||

<iframe | <html><iframe src="https://ourworldindata.org/grapher/co2-concentration-long-term" style="width: 100%; height: 600px; border: 0px none;"></iframe></html> | ||

< | </p><hr><h1 id="basic-intro-to-units-and-measurement">Other greenhouse gases</h1><p>Greenhouse gases are released when stuff is burnt as well as the product of other chemical reactions in industry. Generally, we’re talking about mostly carbon dioxide (<b>CO<sub>2</sub></b>), methane (natural gas) (<b>CH<sub>4</sub></b>), and nitrous oxide (<b>N<sub>2</sub>O</b>). N<sub>2</sub>O and CH<sub>4</sub> are more potent greenhouse gases, but they occur in an order of magnitude less quantity than CO<sub>2</sub>, so removing them is generally much harder. Methane also has a much shorter half life in the atmosphere than CO<sub>2</sub>.</p><h1 id="do-we-really-need-to-remove-co2">Do we really need to remove CO<sub>2</sub>?</h1><p>In the 90s, negative emissions were not [[wikipedia:Overton_window|mainstream]] apart from early research by [[wikipedia:David_Keith_(scientist)|David Keith]], [[wikipedia:Klaus_Lackner|Klaus Lackner]], and others.</p><p>There was some combination of optimism that the problem wasn’t so bad, that the world would decarbonize at a sufficient rate that negative emissions wouldn’t be necessary, and that a policy framework would force action (large scale carbon price/cap and trade, which still doesn’t exist worldwide). This was all combined with fears that negative emissions present a moral hazard by giving ourselves an “out” for crucial emissions reduction work. </p><p>In an attempt to hit a 2 degree warming target, the [https://unfccc.int/process-and-meetings/the-paris-agreement/the-paris-agreement Paris agreement] calls on countries to set “Nationally Determined Contributions”, or [https://unfccc.int/process-and-meetings/the-paris-agreement/nationally-determined-contributions-ndcs NDCs] - commitments to a specific amount of emissions reduction over the coming decades. <b>But these commitments are not even close to enough:</b></p> | ||

<HTML><iframe scrolling="no" frameborder="0" marginheight="0px" marginwidth="0px" style="background: #fff; display: initial; margin: 0 auto;" src="https://cbhighcharts2019.s3.eu-west-2.amazonaws.com/UNEP+Emissions+Gap/emissions_gap.html" width="100%" height="600px"></iframe></HTML> | |||

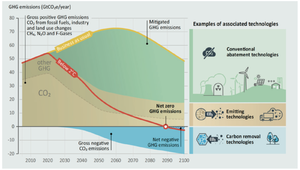

<h4 id="there-are-two-complementary-scary-things-about-this-chart-">There are two complementary scary things about this chart:</h4>[[File:GHG.png|alt=GHG|frameless|300x300px|right|'''Figure 2'''. Projecting future CO<sub>2</sub>.]]<ul><li>All existing Paris commitments (“NDCs” in the above figure) don’t get us even close to a 2 degree trajectory</li><li>Countries are [https://climateactiontracker.org/countries not even close to on track to hit even these commitments]. This is an incredible collective action problem — each individual country faces minimal/zero “''official''” consequences for failing to do so.</li></ul> | |||

<h3 id="putting-this-all-together-is-this-figure-">To illustrate this:</h3> | |||

<p>Compounding the urgency, that research into negative emissions technologies (NETs) have been <b>dramatically underfunded in proportion to their importance</b><i>. </i>To quote the National Academies (emphasis mine):</p><blockquote>“...the federal government spent more than $22 billion on renewable energy research and development from 1978 to 2013. <b>NETs have not received comparable public investment</b> despite expectations that they might provide ~30 percent of the net emissions reductions required this century (i.e., maxima of 20 Gt/y CO<sub>2</sub> of negative emissions and 50 Gt/y CO<sub>2</sub> of mitigation in Figure S.1). <b>NETs are essential to offset greenhouse gas emissions that cannot be eliminated</b>, such as a large fraction of agricultural nitrous oxide and methane emissions.”</blockquote><hr><h1 id="how-to-take-co2-out-of-the-sky">How to take CO<sub>2</sub> out of the sky</h1><p>For a more comprehensive but still accessible overview, I recommend [https://longitudinal.blog/co2-series-part-2-co2-removal/ Adam Marblestone’s Climate Technology Primer]</a> '''and the [https://www.nap.edu/read/25259/chapter/2 Summary section] of the National Academies Report'''.</p><h3 id="briefly-there-are-plant-based-mineral-based-and-chemical-options-">Briefly: there are plant-based, mineral-based, and chemical options.</h3> | |||

[[File:CO2 Capture.png|alt=CO2 Capture|thumb|'''Figure 3'''. The different methods of CO<sub>2</sub> capture.]] | |||

<p>Plant based solutions leverage a plant’s capacity to capture carbon via photosynthesis and the energy of the sun. Solutions in this category include (re)forestation, soil carbon sequestration, algae/kelp farming, and bio-energy with carbon capture and storage (often referred to as BECCS, this is basically a biomass power plant that burns wood and then is fitted with a carbon capture device to handle the smoke aka “[[wikipedia:Flue_gas|flue gas]]").</p> | |||

[[File:IPCC-Soil-Sequestration-Chart.png|alt=IPCC-Soil-Sequestration-Chart|thumb|'''Figure 4'''. Carbon storage techniques.]] | |||

<p>Mineral-based solutions include speeding the weathering of naturally occurring rocks, e.g. [https://projectvesta.org Olivine].</p><p>Chemical solutions include [[wikipedia:Direct_air_capture|Direct Air Capture]] (typically coupled with [https://www.epa.gov/uic/background-information-about-geologic-sequestration geologic storage], the capture aspect is often referred to as DAC), where a big machine sucks CO<sub>2</sub> out of the air; providing gaseous concentrated CO<sub>2</sub> that can then be [https://www.carbfix.com injected underground].</p>These solutions all have different technical tradeoffs, potentials for scale, costs, adoption curves, and more.<hr><h1 id="overview-of-approaches">Overview of approaches</h1><h2 id="trees-and-forests">Trees and forests</h2><p>Trees and plants are incredible at carbon capture, doing so for [[wikipedia:Photosynthesis|“free” via the energy of the sun]] despite how dilute CO<sub>2</sub> is in the atmosphere. The CO<sub>2</sub> trees absorb doesn’t magically go away. Instead, the C literally becomes part of the biomass of the tree. When a tree burns down, the carbon it absorbed is released right back into the air. For permanent sequestration, we’ll need to do something with the biomass of the forest. This could include making it into wooden building materials, biochar fertilizer, or dropping the biomass in the ocean. Or, if the forest is well managed, it can grow for centuries; and we can consider the sequestration “durable” as long as that management persists and is monitored.</p><p>To understand how much carbon is captured, scientists build models that relate easy-to-measure physical properties like diameter and height to the actual above-ground dry weight of a tree, about 50% of which is carbon. These are known as the[https://www.fs.usda.gov/treesearch/pubs/6996 allometric equations]. More modern techniques [https://pachama.com leveraging remote sensing and LIDAR] are being explored to do the same thing with fewer ground measurements.</p><p>Forests take up land that may be more economical if used for other things. Forests are dark colored and may actually decrease [[wikipedia:Albedo|albedo]](light-colored-ness -> heat reflectance from the sun), somewhat decreasing their utility (paper is [https://journals.ametsoc.org/doi/10.1175/JCLI-D-18-0812.1 here] and [http://faculty.washington.edu/aswann/ here’s] a lab working on albedo). There may also be impacts on the biodiversity of the ecosystem the land would otherwise be used for.</p><h2 id="direct-air-capture-dac-sequestration">Direct air capture (DAC) + sequestration</h2>Traditional direct air capture facilities pass atmospheric air through a “sorbent” that absorbs, concentrates, and then controls release of CO2. <b>For a detailed but still accessible overview of the field, see [https://www.frontiersin.org/articles/10.3389/fclim.2019.00010/full The Role of Direct Air Capture in Mitigation of Anthropogenic Greenhouse Gas Emissions].</b><p>Companies currently working on this include [http://climeworks.com Climeworks], [https://carbonengineering.com Carbon Engineering], and [https://globalthermostat.com Global Thermostat]. Because CO<sub>2</sub> is so dilute (about 0.04% in atmospheric air), this process is energy intensive (22kJ/mol). Hence, Lifecycle Analysis is very important. For an example methodology, see [https://www.cell.com/joule/pdf/S2542-4351(18)30225-3.pdf Keith 2018] which describes Carbon Engineerings technical approach.</p><p>There are also some new DAC approaches, currently in the research phase, e.g. [http://news.mit.edu/2019/mit-engineers-develop-new-way-remove-carbon-dioxide-air-1025 electro-swing adsorption] ([https://pubs.rsc.org/en/content/articlelanding/2019/ee/c9ee02412c#!divAbstract news article with a good summary]. These are promising but quite early!</p><p><b>In any case, the result of DAC is pure gaseous CO<sub>2</sub>, which can be either <i>utilized </i>or <i>sequestered</i>.</b></p><h4 id="sequestration">Sequestration</h4><p>Sequestering it means permanently removing the CO<sub>2</sub> from the carbon cycle, and literally reducing the concentration of CO<sub>2</sub> in the atmosphere. This can be done by injecting the CO<sub>2</sub> injected underground into an oil well, salt dome, or saline aquifer.</p><p>It’s fairly straightforward to measure how much CO<sub>2</sub> is being pumped into geologic storage, and there are generally accepted practices in the oil industry to demonstrate secure storage. See the <i>Geologic sequestration - "in situ" </i>subsection of the <i>Enhanced weathering and carbon mineralization </i>section later down this blog post for more details.</p><h4 id="utilization">Utilization</h4><p>Alternatively, this CO<sub>2</sub> can also be <i>utilized</i>. Some utilization mechanisms can be considered negative emissions/long-term sequestration, eg using the CO<sub>2</sub> to [http://www.carboncure.com cure cement]. Other use cases include making [https://www.prometheusfuels.com fuels] and [http://www.opus-12.com chemicals]. The fuels case is interesting, in that the emissions from the fuel wouldn’t cause an absolute increase in atmospheric CO<sub>2</sub> like it would if you pulled the fuel out of the ground. In a sense, you’re burning and “''unburning''” the fuel via capture, concentration, and fuel reformation.</p><h2 id="soils">Soils</h2><p>Soil carbon sequestration methods aim to encourage modified agricultural techniques that increase the carbon sequestered in soil without reducing or otherwise affecting agricultural yield. </p><p>These [https://www.climaterealityproject.org/blog/what-regenerative-agriculture regenerative] mechanisms include no-till farming, using cover crops, and reducing usage of nitrogen fertilizers can enable storage in soil of some of the plant’s carbon volume.</p><p>[https://csiropedia.csiro.au/wp-content/uploads/2016/06/SAF-SCaRP-methods.pdf Measuring soil carbon] can be complex and has high variance: there’s the carbon in the biomass of the plant roots, and then the carbon expelled by the roots that can become stable in the soil as [https://source.colostate.edu/soil-carbon-is-a-valuable-resource-but-all-soil-carbon-is-not-created-equal Soil Organic Carbon]. Ground measurements are expensive (you take a core sample of the soil and stick it in a spectrometer, which is not a thing that farmers have lying around), and it’s still very early for soil carbon remote sensing.</p><p>Remote sensing is tough with soil because you do not just care about the carbon content of the topsoil, you care about the distribution of carbon vertically down the soil column for a couple feet – generally the deeper the carbon is, the more durably it is stored.</p><h2 id="doing-things-with-biomass-bio-energy-with-carbon-capture-and-storage-beccs-and-biochar">Doing things with biomass: Bio energy with carbon capture and storage (BECCS) and Biochar</h2><h3 id="beccs">BECCS</h3>The idea of biomass power in general is that instead of burning coal or natural gas to turn a turbine, you burn biomass (which, because it is biomass, is made of carbon that used to be in the atmosphere).<p>Hence BECCS, as [https://www.draxbiomass.com generally proposed], takes the “get the capture for free!” idea of plant-based carbon capture and combines it with "sequester the flue gas CO<sub>2</sub>" idea that’s often applied to the CO<sub>2</sub> resulting from DAC.</p><p>BECCS strengths and weaknesses are similar to that of forests, where trees and grasses continue to be amazing at “free” carbon capture. The land use needed may be quite large, and likely more agriculturally intense. BECCS requires a very high volume of biomass (and hence has high sequestration potential, but is only currently deployed at very limited scale).</p><p>Depending on how you have combusted or <a href="https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Pyrolysis">pyrolyzed</a> biomass, you either end up with a stream of flue gas from which you can concentrate the CO<sub>2</sub> and do geologic storage/utilization/anything else you would do with flue gas, or you are able to keep the C in the biomass via pyrolysis and output Biochar (see below) – this is what some new BECCS companies like do.</p><h3 id="biochar">Biochar</h3><p>Another option is taking biomass and making [[wikipedia:Biochar|biochar]], generally via [[wikipedia:Pyrolysis|pyrolysis]]. The idea here is that you heat biomass to a high temperature in a low-oxygen environment; producing biochar: a chalky black material that is nearly pure carbon.</p><p>Biochar is used as a fertilizer and soil additive: it seems like it might improve fertility, [https://www.nature.com/articles/srep25127 increase soil organic carbon (SOC)], and reduce soil heavy metal concentrations. <b>For a more detailed overview, see the "Biochar Additions" section of [https://www.frontiersin.org/articles/10.3389/fclim.2019.00008/full Soil C Sequestration as a Biological Negative Emission Strategy].</b></p><p>Properly produced biochar has the potential to remain durable (keep the C sequestered) in soil for an extended period; however its durability is subject to similar environmental conditions as Soil Organic Carbon, particularly precipitation and soil water content as it relates to microbial decay. It may also have positive effects by reducing soil N<sub>2</sub>O emissions (another potent greenhouse gas).</p><h2 id="enhanced-weathering-and-carbon-mineralization">Enhanced weathering and carbon mineralization</h2><h3 id="enhanced-weathering-ex-situ">Enhanced weathering – "ex situ"</h3><p><a href="https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Ultramafic_rock">Common rocks</a> form carbonate minerals when exposed to CO<sub>2</sub>; often even at atmospheric concentrations; permanently binding the C as a mineral (eg CaCO<sub>3</sub> calcium carbonate).</p><p>On geologic timescales, <a href="https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Carbonate–silicate_cycle">this process</a> could restore earth to pre-industrial CO<sub>2</sub> levels. The idea behind "enhanced weathering" is to dramatically accelerate this natural process. <a href="http://projectvesta.org">Project Vestas</a> website provides an accessible walkthrough to this idea. This is sometimes referred to as "ex situ" mineralization because you are mining rocks and putting them through a sped-up carbon mineralization process aboveground.</p><h3 id="geologic-sequestration-in-situ">Geologic sequestration - "in situ"</h3><p>You can think of "in-situ" mineralization as the geologic sequestration component that is crucial to DAC systems.</p><p>It happens when you inject a stream of CO<sub>2</sub> into the right sorts of geologic formations, and [https://science.sciencemag.org/content/352/6291/1312 permanently stores the CO<sub>2</sub> in a mineral]. Its called "in-situ" because you are injecting CO<sub>2</sub> to where the rock already is, instead of bringing the rock above ground and exposing it to atmospheric air.</p><hr><h1 id="lifecycle-analysis-and-tradeoffs-of-carbon-removal-approaches">Lifecycle analysis and tradeoffs of carbon removal approaches</h1><p>It’s important to interpret all carbon removal solutions through a lens of a full lifecycle analysis, which can help answer the question: <b>is the entire operation of a given negative emissions solution net-negative?</b></p><p>For BECCS, for example, this analysis would include the greenhouse gas emissions to grow the biomass, the emissions of building the BECCS plant, the emissions of transporting the biomass to the plant, any loss of CO<sub>2</sub> to inefficiencies in the carbon capture system, and the emissions associated with the energy to run the big machine to pump the CO<sub>2</sub> underground.</p><p>All of this would need to<b> add up to less</b> than the volume of CO<sub>2</sub> sequestered -- ideally much less</p><hr><h1 id="conclusion">Conclusion</h1><p>Here’s what I hope you remember from this piece:</p><ul><li>10-gigaton-scale negative emissions are necessary in essentially every emissions reduction scenario. We have no choice but to fund, research, and deploy them if we’re serious about keeping warming to 2 degrees; or close to it. We are not even close to on track.</li><li>Negative emissions have been dramatically underfunded in proportion to their importance. This needs to be fixed if we’re going to have a shot at reducing the cost enough to make 10-gigaton-scale deployment possible by midcentury. It will take likely take years or decades for basic research and pilot projects to scale and get cheap enough; so we need to start right now.</li><li>It’s very unlikely any one category of technology, or any one natural approach, will scale enough. We should think of a portfolio across all the approaches outlined here, as well as more I didn’t discuss or have yet to be discovered.</li><li>We face the defining problem of our generation; of the entire human project thus far. Climate spans physics, chemistry, ecology, geology, policy, technology, land use, human rights, and more. It’s time we take this seriously as a gigantic opportunity for human progress, and rally to solve it!</li></ul><hr><p>Many people provided feedback on this post, and many more spent time with me over the last few months to help me learn about this field, check my assumptions, and frame my thinking. Thanks in particular to Jeremy Freeman, Christian Anderson, Clay Dumas, Sarah Sclarsic, Peter Reinhardt, Adam Marblestone, Maddie Hall, Klaus Lackner, Nat Keohane, Jennifer Wilcox, Jane Zelikova, Jason Jacobs, April Underwood, Celine Halioua, Florent Crivello, Steve Pacala, Brian Heligman, Michael Nielsen, Jose Luis Ricon, Steve Hamburg, Erika Reinhardt, Alexey Guzey, Ramez Naam, Raylene Yung, Noah Deich, Andrew Bergman, Phil Renforth, Greg Dipple, Giana Amandour, Mason Hartman, Landon Brand, Julio Freedman, Zara Heureux, Jeremy Büttner, Nan Ransohoff, Tamara Winter, and many many more than I could mention here!</p><p>One of the reasons I’ve had so much fun learning about climate is because the people working on it are really great!</p><img src="https://burnzero.com/images/logo.jpg" alt="Snow" style="width:400"><div class="row"><div class="column"> | |||

<a href="https://www.mirror.co.uk/"><img src="https://burnzero.com/images/bluePill.png" alt="Close" style="width:200;float:left"></a> | <a href="https://www.mirror.co.uk/"><img src="https://burnzero.com/images/bluePill.png" alt="Close" style="width:200;float:left"></a> | ||

</div><div class="column"> | </div><div class="column"> | ||

Latest revision as of 03:55, 17 August 2022

Since the industrial revolution, people have been burning an increasing amount of stuff. From little fires in cars to big fires in power plants, we are putting so much of these gases into the sky that we are changing the thermal properties of our atmosphere, trapping ever more heat. This is the greenhouse effect, which is the main contributor to climate change.

Beyond power and transportation, there are less obvious emissions sources as well:

cement production

steel production

agricultural emissions (soil nitrous oxide, animal methane)

You can explore the full range here.

Some sectors have clear paths to reduce emissions: electric vehicles, solar/wind/nuclear, however some will be slower or more complex to decarbonize:

Some agricultural emissions, methane.

Recent data shows progress is too slow. To keep below two degrees, we will need to dramatically reduce current emissions and simultaneously remove 10-15 gigatons of CO2/yr from the atmosphere by 2050 and scale that to about 20+ gigatons annually by 2100. Depending on how quickly we reduce emissions, the amount we need to remove from the atmosphere scales proportionally.

Greenhouse gas emissions are described in units of tons. It’s hard to think about how much “a ton of gas” really is -- this is how big, at surface temperature and pressure. Here’s an animated video visualizing a bunch of these one-ton balls in New York City.

You may also hear people talk about “400 parts per million CO2” or similar. This maps directly to the amount of gas emitted: when emissions mix into the atmosphere, we reference concentrations of the emitted gas as a portion of the atmosphere. This is like stirring sugar into a cup of coffee. For every million parts atmosphere there are 400 parts CO2 this proportion has been rising steadily exactly since the industrial revolution...

Other greenhouse gases

Greenhouse gases are released when stuff is burnt as well as the product of other chemical reactions in industry. Generally, we’re talking about mostly carbon dioxide (CO2), methane (natural gas) (CH4), and nitrous oxide (N2O). N2O and CH4 are more potent greenhouse gases, but they occur in an order of magnitude less quantity than CO2, so removing them is generally much harder. Methane also has a much shorter half life in the atmosphere than CO2.

Do we really need to remove CO2?

In the 90s, negative emissions were not mainstream apart from early research by David Keith, Klaus Lackner, and others.

There was some combination of optimism that the problem wasn’t so bad, that the world would decarbonize at a sufficient rate that negative emissions wouldn’t be necessary, and that a policy framework would force action (large scale carbon price/cap and trade, which still doesn’t exist worldwide). This was all combined with fears that negative emissions present a moral hazard by giving ourselves an “out” for crucial emissions reduction work.

In an attempt to hit a 2 degree warming target, the Paris agreement calls on countries to set “Nationally Determined Contributions”, or NDCs - commitments to a specific amount of emissions reduction over the coming decades. But these commitments are not even close to enough:

There are two complementary scary things about this chart:

- All existing Paris commitments (“NDCs” in the above figure) don’t get us even close to a 2 degree trajectory

- Countries are not even close to on track to hit even these commitments. This is an incredible collective action problem — each individual country faces minimal/zero “official” consequences for failing to do so.

To illustrate this:

Compounding the urgency, that research into negative emissions technologies (NETs) have been dramatically underfunded in proportion to their importance. To quote the National Academies (emphasis mine):

“...the federal government spent more than $22 billion on renewable energy research and development from 1978 to 2013. NETs have not received comparable public investment despite expectations that they might provide ~30 percent of the net emissions reductions required this century (i.e., maxima of 20 Gt/y CO2 of negative emissions and 50 Gt/y CO2 of mitigation in Figure S.1). NETs are essential to offset greenhouse gas emissions that cannot be eliminated, such as a large fraction of agricultural nitrous oxide and methane emissions.”

How to take CO2 out of the sky

For a more comprehensive but still accessible overview, I recommend Adam Marblestone’s Climate Technology Primer</a> and the Summary section of the National Academies Report.

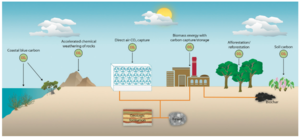

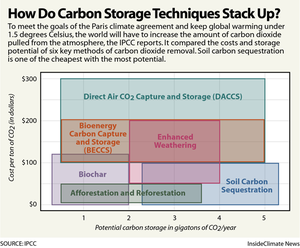

Briefly: there are plant-based, mineral-based, and chemical options.

Plant based solutions leverage a plant’s capacity to capture carbon via photosynthesis and the energy of the sun. Solutions in this category include (re)forestation, soil carbon sequestration, algae/kelp farming, and bio-energy with carbon capture and storage (often referred to as BECCS, this is basically a biomass power plant that burns wood and then is fitted with a carbon capture device to handle the smoke aka “flue gas").

Mineral-based solutions include speeding the weathering of naturally occurring rocks, e.g. Olivine.

Chemical solutions include Direct Air Capture (typically coupled with geologic storage, the capture aspect is often referred to as DAC), where a big machine sucks CO2 out of the air; providing gaseous concentrated CO2 that can then be injected underground.

These solutions all have different technical tradeoffs, potentials for scale, costs, adoption curves, and more.

Overview of approaches

Trees and forests

Trees and plants are incredible at carbon capture, doing so for “free” via the energy of the sun despite how dilute CO2 is in the atmosphere. The CO2 trees absorb doesn’t magically go away. Instead, the C literally becomes part of the biomass of the tree. When a tree burns down, the carbon it absorbed is released right back into the air. For permanent sequestration, we’ll need to do something with the biomass of the forest. This could include making it into wooden building materials, biochar fertilizer, or dropping the biomass in the ocean. Or, if the forest is well managed, it can grow for centuries; and we can consider the sequestration “durable” as long as that management persists and is monitored.

To understand how much carbon is captured, scientists build models that relate easy-to-measure physical properties like diameter and height to the actual above-ground dry weight of a tree, about 50% of which is carbon. These are known as theallometric equations. More modern techniques leveraging remote sensing and LIDAR are being explored to do the same thing with fewer ground measurements.

Forests take up land that may be more economical if used for other things. Forests are dark colored and may actually decrease albedo(light-colored-ness -> heat reflectance from the sun), somewhat decreasing their utility (paper is here and here’s a lab working on albedo). There may also be impacts on the biodiversity of the ecosystem the land would otherwise be used for.

Direct air capture (DAC) + sequestration

Traditional direct air capture facilities pass atmospheric air through a “sorbent” that absorbs, concentrates, and then controls release of CO2. For a detailed but still accessible overview of the field, see The Role of Direct Air Capture in Mitigation of Anthropogenic Greenhouse Gas Emissions.

Companies currently working on this include Climeworks, Carbon Engineering, and Global Thermostat. Because CO2 is so dilute (about 0.04% in atmospheric air), this process is energy intensive (22kJ/mol). Hence, Lifecycle Analysis is very important. For an example methodology, see Keith 2018 which describes Carbon Engineerings technical approach.

There are also some new DAC approaches, currently in the research phase, e.g. electro-swing adsorption (news article with a good summary. These are promising but quite early!

In any case, the result of DAC is pure gaseous CO2, which can be either utilized or sequestered.

Sequestration

Sequestering it means permanently removing the CO2 from the carbon cycle, and literally reducing the concentration of CO2 in the atmosphere. This can be done by injecting the CO2 injected underground into an oil well, salt dome, or saline aquifer.

It’s fairly straightforward to measure how much CO2 is being pumped into geologic storage, and there are generally accepted practices in the oil industry to demonstrate secure storage. See the Geologic sequestration - "in situ" subsection of the Enhanced weathering and carbon mineralization section later down this blog post for more details.

Utilization

Alternatively, this CO2 can also be utilized. Some utilization mechanisms can be considered negative emissions/long-term sequestration, eg using the CO2 to cure cement. Other use cases include making fuels and chemicals. The fuels case is interesting, in that the emissions from the fuel wouldn’t cause an absolute increase in atmospheric CO2 like it would if you pulled the fuel out of the ground. In a sense, you’re burning and “unburning” the fuel via capture, concentration, and fuel reformation.

Soils

Soil carbon sequestration methods aim to encourage modified agricultural techniques that increase the carbon sequestered in soil without reducing or otherwise affecting agricultural yield.

These regenerative mechanisms include no-till farming, using cover crops, and reducing usage of nitrogen fertilizers can enable storage in soil of some of the plant’s carbon volume.

Measuring soil carbon can be complex and has high variance: there’s the carbon in the biomass of the plant roots, and then the carbon expelled by the roots that can become stable in the soil as Soil Organic Carbon. Ground measurements are expensive (you take a core sample of the soil and stick it in a spectrometer, which is not a thing that farmers have lying around), and it’s still very early for soil carbon remote sensing.

Remote sensing is tough with soil because you do not just care about the carbon content of the topsoil, you care about the distribution of carbon vertically down the soil column for a couple feet – generally the deeper the carbon is, the more durably it is stored.

Doing things with biomass: Bio energy with carbon capture and storage (BECCS) and Biochar

BECCS

The idea of biomass power in general is that instead of burning coal or natural gas to turn a turbine, you burn biomass (which, because it is biomass, is made of carbon that used to be in the atmosphere).

Hence BECCS, as generally proposed, takes the “get the capture for free!” idea of plant-based carbon capture and combines it with "sequester the flue gas CO2" idea that’s often applied to the CO2 resulting from DAC.

BECCS strengths and weaknesses are similar to that of forests, where trees and grasses continue to be amazing at “free” carbon capture. The land use needed may be quite large, and likely more agriculturally intense. BECCS requires a very high volume of biomass (and hence has high sequestration potential, but is only currently deployed at very limited scale).

Depending on how you have combusted or <a href="https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Pyrolysis">pyrolyzed</a> biomass, you either end up with a stream of flue gas from which you can concentrate the CO2 and do geologic storage/utilization/anything else you would do with flue gas, or you are able to keep the C in the biomass via pyrolysis and output Biochar (see below) – this is what some new BECCS companies like do.

Biochar

Another option is taking biomass and making biochar, generally via pyrolysis. The idea here is that you heat biomass to a high temperature in a low-oxygen environment; producing biochar: a chalky black material that is nearly pure carbon.

Biochar is used as a fertilizer and soil additive: it seems like it might improve fertility, increase soil organic carbon (SOC), and reduce soil heavy metal concentrations. For a more detailed overview, see the "Biochar Additions" section of Soil C Sequestration as a Biological Negative Emission Strategy.

Properly produced biochar has the potential to remain durable (keep the C sequestered) in soil for an extended period; however its durability is subject to similar environmental conditions as Soil Organic Carbon, particularly precipitation and soil water content as it relates to microbial decay. It may also have positive effects by reducing soil N2O emissions (another potent greenhouse gas).

Enhanced weathering and carbon mineralization

Enhanced weathering – "ex situ"

<a href="https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Ultramafic_rock">Common rocks</a> form carbonate minerals when exposed to CO2; often even at atmospheric concentrations; permanently binding the C as a mineral (eg CaCO3 calcium carbonate).

On geologic timescales, <a href="https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Carbonate–silicate_cycle">this process</a> could restore earth to pre-industrial CO2 levels. The idea behind "enhanced weathering" is to dramatically accelerate this natural process. <a href="http://projectvesta.org">Project Vestas</a> website provides an accessible walkthrough to this idea. This is sometimes referred to as "ex situ" mineralization because you are mining rocks and putting them through a sped-up carbon mineralization process aboveground.

Geologic sequestration - "in situ"

You can think of "in-situ" mineralization as the geologic sequestration component that is crucial to DAC systems.

It happens when you inject a stream of CO2 into the right sorts of geologic formations, and permanently stores the CO2 in a mineral. Its called "in-situ" because you are injecting CO2 to where the rock already is, instead of bringing the rock above ground and exposing it to atmospheric air.

Lifecycle analysis and tradeoffs of carbon removal approaches

It’s important to interpret all carbon removal solutions through a lens of a full lifecycle analysis, which can help answer the question: is the entire operation of a given negative emissions solution net-negative?

For BECCS, for example, this analysis would include the greenhouse gas emissions to grow the biomass, the emissions of building the BECCS plant, the emissions of transporting the biomass to the plant, any loss of CO2 to inefficiencies in the carbon capture system, and the emissions associated with the energy to run the big machine to pump the CO2 underground.

All of this would need to add up to less than the volume of CO2 sequestered -- ideally much less

Conclusion

Here’s what I hope you remember from this piece:

- 10-gigaton-scale negative emissions are necessary in essentially every emissions reduction scenario. We have no choice but to fund, research, and deploy them if we’re serious about keeping warming to 2 degrees; or close to it. We are not even close to on track.

- Negative emissions have been dramatically underfunded in proportion to their importance. This needs to be fixed if we’re going to have a shot at reducing the cost enough to make 10-gigaton-scale deployment possible by midcentury. It will take likely take years or decades for basic research and pilot projects to scale and get cheap enough; so we need to start right now.

- It’s very unlikely any one category of technology, or any one natural approach, will scale enough. We should think of a portfolio across all the approaches outlined here, as well as more I didn’t discuss or have yet to be discovered.

- We face the defining problem of our generation; of the entire human project thus far. Climate spans physics, chemistry, ecology, geology, policy, technology, land use, human rights, and more. It’s time we take this seriously as a gigantic opportunity for human progress, and rally to solve it!

Many people provided feedback on this post, and many more spent time with me over the last few months to help me learn about this field, check my assumptions, and frame my thinking. Thanks in particular to Jeremy Freeman, Christian Anderson, Clay Dumas, Sarah Sclarsic, Peter Reinhardt, Adam Marblestone, Maddie Hall, Klaus Lackner, Nat Keohane, Jennifer Wilcox, Jane Zelikova, Jason Jacobs, April Underwood, Celine Halioua, Florent Crivello, Steve Pacala, Brian Heligman, Michael Nielsen, Jose Luis Ricon, Steve Hamburg, Erika Reinhardt, Alexey Guzey, Ramez Naam, Raylene Yung, Noah Deich, Andrew Bergman, Phil Renforth, Greg Dipple, Giana Amandour, Mason Hartman, Landon Brand, Julio Freedman, Zara Heureux, Jeremy Büttner, Nan Ransohoff, Tamara Winter, and many many more than I could mention here!

One of the reasons I’ve had so much fun learning about climate is because the people working on it are really great!

<img src="https://burnzero.com/images/logo.jpg" alt="Snow" style="width:400">

<a href="https://www.mirror.co.uk/"><img src="https://burnzero.com/images/bluePill.png" alt="Close" style="width:200;float:left"></a>

<a href="https://burnzero.com/Books.html"><img src="https://burnzero.com/images/Red_pill.png" alt="Open" style="width:200"></a>

<a href="https://youtu.be/xFhn_GUAhGU">

$*&^choose one wisely@*

</a>

</body>