Amanita muscaria: Difference between revisions

No edit summary |

mNo edit summary |

||

| (49 intermediate revisions by the same user not shown) | |||

| Line 1: | Line 1: | ||

Amanita muscaria (also known as fly agaric | [[File:Amanita as a psychoactive.jpg|alt=Amanita as a psychoactive|thumb|'''Figure 1'''. Amanita Muscaria aka: Fly Agaric, Soma, Toadstool]] | ||

'''''Amanita muscaria'' (also known as the ''fly agaric'' depicted in Figure 1) is a psychoactive mushroom that grows widely in the northern hemisphere. The mushroom is a large white-gilled, white-spotted, usually red mushroom that is one of the most recognizable and widely encountered in popular culture 🍄.''' The mushroom is arguably<ref>Soma and "Amanita muscaria" Author(s): John Brough Source: Bulletin of the School of Oriental and African Studies, University of London, Vol. 34, No. 2 (1971), pp. 331-362 Published by: Cambridge University Press on behalf of School of Oriental and African Studies Stable URL: <nowiki>http://www.jstor.org/stable/612695</nowiki></ref> the ''[[Soma]]-plant'' in Vedic religion<ref name=":0">Soma: Divine Mushroom of Immortality by R. Gordon Wasson by Sungazer Press (first published January 1st 1968)</ref> as it is noted for its Lilliputian ('''Figure 3''') hallucinatory properties, which derive from its primary psychoactive constituents ibotenic acid and muscimol<ref>Hallucinogenic Species in Amanita Muscaria. Determination of Muscimol and Ibotenic Acid by Ion Interaction HPLC M. C. Gennaro a , D. Giacosa a , E. Gioannini a & S. Angelino a a Università di Torino Dipartimento di Chimica Analitica Via P. Giuria , 5 10125, Torino, Italy Published online: 23 Sep 2006.</ref>. | |||

[[File:Amanita muscaria lookalikes..png|alt=Amanita muscaria lookalikes.|thumb|'''Figure 2'''. Amanita muscaria lookalikes.]] | |||

Although the fresh mushroom is often classified as poisonous<ref>Michelot, D., & Melendez-Howell, L. M. (2003). ''Amanita muscaria: chemistry, biology, toxicology, and ethnomycology. Mycological Research, 107(2), 131–146.'' doi:10.1017/s0953756203007305 </ref>, reports of human deaths resulting from its ingestion are extremely rare<ref>Fly agaric (Amanita muscaria) poisoning, case report and review Leszek Satora*, Dorota Pach, Beata Butryn, Piotr Hydzik, Barbara Balicka-S´lusarczyk Department of Clinical Toxicology, Poison Information Center, Collegium Medicum, Jagiellonian University, Os. Złotej Jesieni 1, 31-826 Krako´w, Poland Received 12 November 2004; accepted 10 January 2005 Available online 14 April 2005</ref>. Furthermore, there are a multitude of recorded cases of low dose ingestion without issue<ref>Buck, R. W. (1963). ''Toxicity of Amanita muscaria. JAMA: The Journal of the American Medical Association, 185(8), 663.'' doi:10.1001/jama.1963.03060080059020 </ref>. The key to its safety is differentiation from the Destroying Angel and the Death Cap, parboiling—which weakens its toxicity and breaks down the mushroom's psychoactive substances and careful dosage<ref>Neuropharmacological Investigations on Muscimol, | |||

a Psychotropic Drug Extracted from Amanita Muscaria* | |||

A. Sco~TI DE CA~OHS, F. LIPPA/~INI and V. G. LONGO Laboratori di Chimica Terapeutica, Istituto Superiore di Sanit&, Roma, Italia | |||

Received March 10, 1969</ref>. To this day, the dried mushroom is used as a medicinal ingredient, and as a substitute for alcohol in parts of Russia as a narcotic by the Koryak people<ref>Russian Use of Amanita muscaria: A Footnote to Wasson's Soma Author(s): Ethel Dunn Source: Current Anthropology, Vol. 14, No. 4 (Oct., 1973), pp. 488-492 Published by: The University of Chicago Press on behalf of Wenner-Gren Foundation for Anthropological Research Stable URL: <nowiki>http://www.jstor.org/stable/2740856</nowiki> . Accessed: 16/02/2015 19:02</ref>. | |||

Amanita muscaria mushrooms are not known to be addictive or dependence-forming, and reports even show that desire to redose goes down with usage, though there is no research on this topic. | == Differentiation == | ||

One of the major dangers of ''amanita muscaria'' is misidentifying it as a different species of mushroom. Several other mushrooms in the genus amanita are toxic and cause 90% of all fatal mushroom poisonings see '''Figure 2'''. One such mushroom, the amanita phalloides, better known as the death cap, which contains α-amanitin and β-Amanitin, both of which are extremely potent RNA polymerase II and RNA polymerase III inhibitors which damage virtually every tissue in the body. As the name suggests, the ''amanita muscaria'' contains the chemical muscarine, a muscarinic acetylcholine agonist which is known to cause seizures; however, the mushroom contains very low amounts that are highly unlikely to pose any significant harm. | |||

== Identification == | |||

Found in forests from July to October, this Amanita has a symbiotic relationship with various trees and is most often found under pines, spruces, and birches. The problem with the identification of the Amanita (and this is a general mushroom rule) is that rain may alter its appearance considerably by washing away its patches or draining its vibrant red to a paler shade. With these more superficial characteristics erased, it can easily be mistaken for an innocuous or edible look-alike. Beware of look-alikes! | |||

== Ingestion == | |||

There is a long history of edibility of the prepared mushroom in Japan<ref>"Amanita muscaria": The Gorgeous Mushroom Author(s): Christal Whelan Source: Asian Folklore Studies, Vol. 53, No. 1 (1994), pp. 163-167 Published by: Nanzan University Stable URL: <nowiki>http://www.jstor.org/stable/1178564</nowiki> . Accessed: 18/06/2014 00:23</ref>. Traditional knowledge highlighted that in its raw state this mushroom is toxic and inebriating and therefore did not ingest it as such. They consumed it only after certain preparations: "Dried, soaked in brine for 12-13 weeks, rinsed in successive washings until the water became clear. They came out alabaster white and indeed are translucent like alabaster. Prepared thus for savouring during the long winter evenings, they are delicious, excellent as hors d'oeuvres" | |||

=== Pharmacology === | |||

[[File:Lilliputian hallucinations.jpg|alt=Lilliputian hallucinations|thumb|'''Figure 3'''. Lilliputian hallucinations]] | |||

The active ingredients of the Amanita muscaria are ibotenic acid, muscimol, and muscarine the highest concentration of which is in the yellow tissue of the cap immediately below the skin<ref>United Nations, Amanita muscaria : present understanding of its chemistry Accessed on 18th Jun 2022 via<nowiki/>https://www.unodc.org/unodc/en/data-and-analysis/bulletin/bulletin_1970-01-01_4_page005.html</ref>. The first two ingredients act on the nervous system as GABA-A agonists within thirty minutes to two hours after ingestion, causing dizziness, lack of coordination, delirium, spasms, and muscular cramps. These symptoms are temporary and subside within four to twenty-four hours. There is some evidence to suggest that the reported lilliputian [[hallucinations]] (see '''Figure 3''') mimic Z-drug side effects<ref>Tsai MJ, Huang YB, Wu PC. A novel clinical pattern of visual hallucination after zolpidem use. J Toxicol Clin Toxicol. 2003;41:869–72.</ref><ref>Coleman DE, Ota K. Hallucinations with zolpidem and fluoxetine in an impaired driver. J Forensic Sci. 2004;49:392–3.</ref><ref>Kito S, Koga Y. Visual hallucinations and amnesia associated with zolpidem triggered by fluvoxamine: A possible interaction. Int Psychogeriatr. 2006;18:749–51.</ref><ref>Elko CJ, Burgess JL, Robertson WO. Zolpidem-associated hallucinations and serotonin reuptake inhibition: A possible interaction. J Toxicol Clin Toxicol. 1998;36:195–203.</ref><ref>'''Zolpidem-induced Hallucinations''': A Brief Case Report from the Indian Subcontinent. Gurvinder Pal Singh and Neeraj Loona. Indian J Psychol Med. 2013 Apr-Jun; 35(2): 212–213. doi: 10.4103/0253-7176.116260</ref>. | |||

==== Toxicity ==== | |||

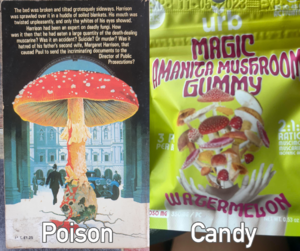

[[File:Amanita muscaria.png|alt=Amanita muscaria|thumb|'''Figure 4'''. Poison or Candy?]] | |||

If prepared incorrectly amanita muscaria is potentially toxic. Ibotenic acid contained within the fresh mushroom is known to be a neurotoxin, acting via the NMDA receptor and metabotropic glutamate receptor. Ibotenic acid can be converted to muscimol via decarboxylation. This can be performed using a combination of heat and acid-catalysis with the potential for adding decarboxylasing enzymes such as milk / lactobacillus derivatives which contain glutamate decarboxylase. | |||

==== Dose ==== | |||

A medium-size fresh carpophore with a cap diameter of 10-15 cm weighs about 60-70 g. According to literature reports<ref name=":0" />, Siberian mushroom eaters used for moderate effects 1-4 dried mushrooms and 5-10 was considered immoderate use. For dosing, start with a small amount such as 1/4 or 1 teaspoon while you are awake, and see how it affects you. Each new separate day while you are awake, increase the amount by a little until you then have the dose or dose range you want to experiment with. If your liquid is extra potent you can experiment with this same liquid at expected dosing for several weeks (or all year if used infrequently). Effects will typically begin anywhere from 15 to 120 minutes after consumption. | |||

Small-dose effects can include mild to moderate relaxing euphoria and warm body sensations, increased ability to meditate, as well as light muscle spasms and a somewhat energetic feeling, soon followed by a sense of peace and sleepiness. Sleep can be renewing, with intense, vivid dreams that are difficult to recall in detail upon waking. It can also significantly reduce the number of times one wakes up during sleep. | |||

==== '''Contraindications''' ==== | |||

It may be harmful to combine ''Amanita muscaria'' constituents with other GABAergic depressants such as alcohol, benzodiazepines or barbiturates. ''Amanita muscaria'' mushrooms are not known to be addictive or dependence-forming, and reports even show that the desire to redose goes down with usage, though there is no research on this topic. | |||

== Effect == | |||

Muscimol as a potent, selective agonist for the GABA-A receptors displays sedative-hypnotic, depressant and hallucinogenic psychoactivity. | |||

=== Hallucinations === | |||

Lilliputian [[hallucinations]] concern hallucinated human, animal or fantasy entities of minute size. They have been reported anecdotally for millennia however, in the 1960s while the number of medical publications on lilliputian hallucinations had dwindled, young people became fascinated with records of ancient shamanic traditions and expressed a longing to encounter the sentient, discarnate beings described after the use of [[psychedelics]]<ref name=":1">The Invisible Landscape: Mind, Hallucinogens, and the I Ching, Terence Mckenna, published in 1993, ISBN 0062506358</ref>. | |||

A modern retrospective analysis of scientific data shows descriptions of the ‘fly-agaric men’ and ‘amanita girls’ evoked by the mushroom Amanita muscaria show striking similarities to Leroy’s lilliputian hallucinations<ref>The Encyclopedia of Psychoactive Substances, Richard Rudgley, St. Martin's Publishing Group, 2014, ISBN: 1466886005</ref>. The same holds true for Chinese descriptions of xiao ren ren (‘lots of little people’), prompted by the consumption of undercooked blue-staining boletes<ref>Xiao Ren Ren : The “Little People” of Yunnan, November 2008Economic Botany 62(3):540-544, DOI:10.1007/s12231-008-9049-0</ref>. | |||

However, the "''machine elves''," "''clockwork elves''" and "''gnomes''," seen after taking DMT seem to be substantially different from traditional Lilliputian experiences <ref name=":1" />. The literature on these events, which is commonly referred to as "[[Psychedelics|psychedelic]] entity encounters," describes them as minute, mobile, primarily extraterrestrial, and frequently kaleidoscopically shifting. Their love of connection is another crucial quality<ref>Anomalous Psychedelic Experiences: At the Neurochemical Juncture of the Humanistic and Parapsychological, David Luke, Journal of Humanistic Psychology 2022, Vol. 62(2) 257–297 DOI: 10.1177/0022167820917767</ref>. These "''entities''" are mentioned in half of the accounts of about 60 healthy volunteers who received DMT intravenously, according to a comprehensive medical analysis of them<ref>Psychometric assessment of the Hallucinogen Rating Scale�. Drug and Alcohol Dependence 62 (2001) 215–223. Accessed on 15th August 2022 via <nowiki>https://d1wqtxts1xzle7.cloudfront.net/35874594/riba_dad_2001-with-cover-page-v2.pdf</nowiki></ref>. | |||

According to reports, the creatures frequently lived with the volunteers in a "shared extraterrestrial reality" and probed, examined, tested, and/or modified their brains and bodies. The perception that the entities had been waiting for them to arrive and may have even started the "encounter" was expressed by 69% of respondents to an online poll of 2561 people who had used DMT by inhalation<ref>Survey of entity encounter experiences occasioned by inhaled N,N-dimethyltryptamine: Phenomenology, interpretation, and enduring effects. Alan K Davis, John M Clifton, Eric G Weaver, <nowiki>https://doi.org/10.1177/0269881120916143</nowiki></ref>, demonstrating the reality of this realm. The stereotypical Leroyan experience of brightly coloured small animals marching or dancing around people's actual settings while completely unaware of the - usually puzzled - viewer is obviously very different from these experiences.<hr> | |||

'''References''' | |||

<references /> | |||

Latest revision as of 04:55, 23 March 2024

Amanita muscaria (also known as the fly agaric depicted in Figure 1) is a psychoactive mushroom that grows widely in the northern hemisphere. The mushroom is a large white-gilled, white-spotted, usually red mushroom that is one of the most recognizable and widely encountered in popular culture 🍄. The mushroom is arguably[1] the Soma-plant in Vedic religion[2] as it is noted for its Lilliputian (Figure 3) hallucinatory properties, which derive from its primary psychoactive constituents ibotenic acid and muscimol[3].

Although the fresh mushroom is often classified as poisonous[4], reports of human deaths resulting from its ingestion are extremely rare[5]. Furthermore, there are a multitude of recorded cases of low dose ingestion without issue[6]. The key to its safety is differentiation from the Destroying Angel and the Death Cap, parboiling—which weakens its toxicity and breaks down the mushroom's psychoactive substances and careful dosage[7]. To this day, the dried mushroom is used as a medicinal ingredient, and as a substitute for alcohol in parts of Russia as a narcotic by the Koryak people[8].

Differentiation

One of the major dangers of amanita muscaria is misidentifying it as a different species of mushroom. Several other mushrooms in the genus amanita are toxic and cause 90% of all fatal mushroom poisonings see Figure 2. One such mushroom, the amanita phalloides, better known as the death cap, which contains α-amanitin and β-Amanitin, both of which are extremely potent RNA polymerase II and RNA polymerase III inhibitors which damage virtually every tissue in the body. As the name suggests, the amanita muscaria contains the chemical muscarine, a muscarinic acetylcholine agonist which is known to cause seizures; however, the mushroom contains very low amounts that are highly unlikely to pose any significant harm.

Identification

Found in forests from July to October, this Amanita has a symbiotic relationship with various trees and is most often found under pines, spruces, and birches. The problem with the identification of the Amanita (and this is a general mushroom rule) is that rain may alter its appearance considerably by washing away its patches or draining its vibrant red to a paler shade. With these more superficial characteristics erased, it can easily be mistaken for an innocuous or edible look-alike. Beware of look-alikes!

Ingestion

There is a long history of edibility of the prepared mushroom in Japan[9]. Traditional knowledge highlighted that in its raw state this mushroom is toxic and inebriating and therefore did not ingest it as such. They consumed it only after certain preparations: "Dried, soaked in brine for 12-13 weeks, rinsed in successive washings until the water became clear. They came out alabaster white and indeed are translucent like alabaster. Prepared thus for savouring during the long winter evenings, they are delicious, excellent as hors d'oeuvres"

Pharmacology

The active ingredients of the Amanita muscaria are ibotenic acid, muscimol, and muscarine the highest concentration of which is in the yellow tissue of the cap immediately below the skin[10]. The first two ingredients act on the nervous system as GABA-A agonists within thirty minutes to two hours after ingestion, causing dizziness, lack of coordination, delirium, spasms, and muscular cramps. These symptoms are temporary and subside within four to twenty-four hours. There is some evidence to suggest that the reported lilliputian hallucinations (see Figure 3) mimic Z-drug side effects[11][12][13][14][15].

Toxicity

If prepared incorrectly amanita muscaria is potentially toxic. Ibotenic acid contained within the fresh mushroom is known to be a neurotoxin, acting via the NMDA receptor and metabotropic glutamate receptor. Ibotenic acid can be converted to muscimol via decarboxylation. This can be performed using a combination of heat and acid-catalysis with the potential for adding decarboxylasing enzymes such as milk / lactobacillus derivatives which contain glutamate decarboxylase.

Dose

A medium-size fresh carpophore with a cap diameter of 10-15 cm weighs about 60-70 g. According to literature reports[2], Siberian mushroom eaters used for moderate effects 1-4 dried mushrooms and 5-10 was considered immoderate use. For dosing, start with a small amount such as 1/4 or 1 teaspoon while you are awake, and see how it affects you. Each new separate day while you are awake, increase the amount by a little until you then have the dose or dose range you want to experiment with. If your liquid is extra potent you can experiment with this same liquid at expected dosing for several weeks (or all year if used infrequently). Effects will typically begin anywhere from 15 to 120 minutes after consumption.

Small-dose effects can include mild to moderate relaxing euphoria and warm body sensations, increased ability to meditate, as well as light muscle spasms and a somewhat energetic feeling, soon followed by a sense of peace and sleepiness. Sleep can be renewing, with intense, vivid dreams that are difficult to recall in detail upon waking. It can also significantly reduce the number of times one wakes up during sleep.

Contraindications

It may be harmful to combine Amanita muscaria constituents with other GABAergic depressants such as alcohol, benzodiazepines or barbiturates. Amanita muscaria mushrooms are not known to be addictive or dependence-forming, and reports even show that the desire to redose goes down with usage, though there is no research on this topic.

Effect

Muscimol as a potent, selective agonist for the GABA-A receptors displays sedative-hypnotic, depressant and hallucinogenic psychoactivity.

Hallucinations

Lilliputian hallucinations concern hallucinated human, animal or fantasy entities of minute size. They have been reported anecdotally for millennia however, in the 1960s while the number of medical publications on lilliputian hallucinations had dwindled, young people became fascinated with records of ancient shamanic traditions and expressed a longing to encounter the sentient, discarnate beings described after the use of psychedelics[16].

A modern retrospective analysis of scientific data shows descriptions of the ‘fly-agaric men’ and ‘amanita girls’ evoked by the mushroom Amanita muscaria show striking similarities to Leroy’s lilliputian hallucinations[17]. The same holds true for Chinese descriptions of xiao ren ren (‘lots of little people’), prompted by the consumption of undercooked blue-staining boletes[18].

However, the "machine elves," "clockwork elves" and "gnomes," seen after taking DMT seem to be substantially different from traditional Lilliputian experiences [16]. The literature on these events, which is commonly referred to as "psychedelic entity encounters," describes them as minute, mobile, primarily extraterrestrial, and frequently kaleidoscopically shifting. Their love of connection is another crucial quality[19]. These "entities" are mentioned in half of the accounts of about 60 healthy volunteers who received DMT intravenously, according to a comprehensive medical analysis of them[20].

According to reports, the creatures frequently lived with the volunteers in a "shared extraterrestrial reality" and probed, examined, tested, and/or modified their brains and bodies. The perception that the entities had been waiting for them to arrive and may have even started the "encounter" was expressed by 69% of respondents to an online poll of 2561 people who had used DMT by inhalation[21], demonstrating the reality of this realm. The stereotypical Leroyan experience of brightly coloured small animals marching or dancing around people's actual settings while completely unaware of the - usually puzzled - viewer is obviously very different from these experiences.

References

- ↑ Soma and "Amanita muscaria" Author(s): John Brough Source: Bulletin of the School of Oriental and African Studies, University of London, Vol. 34, No. 2 (1971), pp. 331-362 Published by: Cambridge University Press on behalf of School of Oriental and African Studies Stable URL: http://www.jstor.org/stable/612695

- ↑ 2.0 2.1 Soma: Divine Mushroom of Immortality by R. Gordon Wasson by Sungazer Press (first published January 1st 1968)

- ↑ Hallucinogenic Species in Amanita Muscaria. Determination of Muscimol and Ibotenic Acid by Ion Interaction HPLC M. C. Gennaro a , D. Giacosa a , E. Gioannini a & S. Angelino a a Università di Torino Dipartimento di Chimica Analitica Via P. Giuria , 5 10125, Torino, Italy Published online: 23 Sep 2006.

- ↑ Michelot, D., & Melendez-Howell, L. M. (2003). Amanita muscaria: chemistry, biology, toxicology, and ethnomycology. Mycological Research, 107(2), 131–146. doi:10.1017/s0953756203007305

- ↑ Fly agaric (Amanita muscaria) poisoning, case report and review Leszek Satora*, Dorota Pach, Beata Butryn, Piotr Hydzik, Barbara Balicka-S´lusarczyk Department of Clinical Toxicology, Poison Information Center, Collegium Medicum, Jagiellonian University, Os. Złotej Jesieni 1, 31-826 Krako´w, Poland Received 12 November 2004; accepted 10 January 2005 Available online 14 April 2005

- ↑ Buck, R. W. (1963). Toxicity of Amanita muscaria. JAMA: The Journal of the American Medical Association, 185(8), 663. doi:10.1001/jama.1963.03060080059020

- ↑ Neuropharmacological Investigations on Muscimol, a Psychotropic Drug Extracted from Amanita Muscaria* A. Sco~TI DE CA~OHS, F. LIPPA/~INI and V. G. LONGO Laboratori di Chimica Terapeutica, Istituto Superiore di Sanit&, Roma, Italia Received March 10, 1969

- ↑ Russian Use of Amanita muscaria: A Footnote to Wasson's Soma Author(s): Ethel Dunn Source: Current Anthropology, Vol. 14, No. 4 (Oct., 1973), pp. 488-492 Published by: The University of Chicago Press on behalf of Wenner-Gren Foundation for Anthropological Research Stable URL: http://www.jstor.org/stable/2740856 . Accessed: 16/02/2015 19:02

- ↑ "Amanita muscaria": The Gorgeous Mushroom Author(s): Christal Whelan Source: Asian Folklore Studies, Vol. 53, No. 1 (1994), pp. 163-167 Published by: Nanzan University Stable URL: http://www.jstor.org/stable/1178564 . Accessed: 18/06/2014 00:23

- ↑ United Nations, Amanita muscaria : present understanding of its chemistry Accessed on 18th Jun 2022 viahttps://www.unodc.org/unodc/en/data-and-analysis/bulletin/bulletin_1970-01-01_4_page005.html

- ↑ Tsai MJ, Huang YB, Wu PC. A novel clinical pattern of visual hallucination after zolpidem use. J Toxicol Clin Toxicol. 2003;41:869–72.

- ↑ Coleman DE, Ota K. Hallucinations with zolpidem and fluoxetine in an impaired driver. J Forensic Sci. 2004;49:392–3.

- ↑ Kito S, Koga Y. Visual hallucinations and amnesia associated with zolpidem triggered by fluvoxamine: A possible interaction. Int Psychogeriatr. 2006;18:749–51.

- ↑ Elko CJ, Burgess JL, Robertson WO. Zolpidem-associated hallucinations and serotonin reuptake inhibition: A possible interaction. J Toxicol Clin Toxicol. 1998;36:195–203.

- ↑ Zolpidem-induced Hallucinations: A Brief Case Report from the Indian Subcontinent. Gurvinder Pal Singh and Neeraj Loona. Indian J Psychol Med. 2013 Apr-Jun; 35(2): 212–213. doi: 10.4103/0253-7176.116260

- ↑ 16.0 16.1 The Invisible Landscape: Mind, Hallucinogens, and the I Ching, Terence Mckenna, published in 1993, ISBN 0062506358

- ↑ The Encyclopedia of Psychoactive Substances, Richard Rudgley, St. Martin's Publishing Group, 2014, ISBN: 1466886005

- ↑ Xiao Ren Ren : The “Little People” of Yunnan, November 2008Economic Botany 62(3):540-544, DOI:10.1007/s12231-008-9049-0

- ↑ Anomalous Psychedelic Experiences: At the Neurochemical Juncture of the Humanistic and Parapsychological, David Luke, Journal of Humanistic Psychology 2022, Vol. 62(2) 257–297 DOI: 10.1177/0022167820917767

- ↑ Psychometric assessment of the Hallucinogen Rating Scale�. Drug and Alcohol Dependence 62 (2001) 215–223. Accessed on 15th August 2022 via https://d1wqtxts1xzle7.cloudfront.net/35874594/riba_dad_2001-with-cover-page-v2.pdf

- ↑ Survey of entity encounter experiences occasioned by inhaled N,N-dimethyltryptamine: Phenomenology, interpretation, and enduring effects. Alan K Davis, John M Clifton, Eric G Weaver, https://doi.org/10.1177/0269881120916143