Placebo

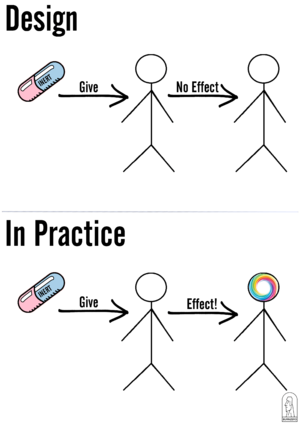

A placebo is a substance or treatment that lacks intrinsic therapeutic value but can still produce real physiological or psychological effects when administered under the belief that it is effective. This phenomenon, known as the placebo effect (see Figure 1), is largely driven by expectation, conditioning, and psychosomatic mechanisms such as priming and the power of suggestion.

History

In 18th-century London, patients paid five guineas for Perkins Tractors — metal rods believed to relieve pain when waved over the body (Figure 2). Remarkably, many reported real relief. British physician John Haygarth later demonstrated that wooden replicas were just as effective, offering one of the earliest scientific validations of the placebo effect.

Variability in Placebo Strength

Placebos today take many forms — from sugar pills to injections — and are not all equally effective. A 2015 study from Tufts Medical Center[1] found that injected placebos were more effective at relieving osteoarthritis pain than topical, which in turn outperformed oral placebos. In fact, the benefit gap between an injection and a pill was wider than between acetaminophen and placebo.

Placebo strength is also influenced by non-drug factors, such as a physician’s warmth and confidence, or even patient demographics. For instance, children often show stronger placebo responses than adults[2], which can skew trial results and obscure actual drug efficacy.

Placebo Augmentation

Placebo augmentation refers to strategies designed to enhance the placebo effect intentionally and ethically — not through deception, but by leveraging what makes placebos work: expectation, context, and meaning. Placebos are often maligned in modern Western medicine as deceptive or inert interventions, however tehy are real, measurable, and neurologically mediated. In studies on psychedelic microdosing, many participants report mood or focus improvements, yet clinical trials often find these match the placebo group — suggesting belief itself may drive much of the benefit.

Clinicians have a long history of research which explores how to amplify placebo responses through intentional design — such as ritual, community setting, and therapeutic framing. This opens a new frontier in care: treatments may be more effective when combined with placebo-enhancing factors. The line between medicine and mindset is blurring — and that may be a good thing.

Here are ten practical ways clinicians can ethically augment placebo effects:

- Foster a strong therapeutic alliance — Build trust and empathy to increase patient confidence in treatment.

- Set positive expectations — Frame interventions with hopeful, realistic language.

- Use meaningful rituals — Repeatable actions, even simple ones, can deepen perceived treatment value.

- Enhance the clinical environment — Calm, clean, and supportive spaces reinforce belief in care quality.

- Use confident, reassuring language — Avoid jargon, emphasize progress, and speak with clarity.

- Personalize the treatment plan — Tailoring care increases psychological engagement.

- Involve patients in decision-making — Shared decisions boost agency and investment in outcomes.

- Provide simple, clear explanations — Understanding how treatment works boosts placebo strength.

- Leverage symbolic cues — Professional dress, branded materials, and tone subtly shape expectations.

- Encourage mindfulness or intention-setting — Framing care as meaningful can boost results.

Why Does the Placebo Effect Exist?

From an evolutionary standpoint, organisms that respond quickly to environmental threats are more likely to survive. Over time, evolution favored systems that could anticipate danger — leading to the brain’s development as a predictive engine. The placebo effect may stem from this capacity: if the brain expects healing, it may trigger internal mechanisms (like endorphin release) in anticipation of the outcome.

This predictive process operates mostly subconsciously. If an incoming stimulus had to be consciously processed before action, survival could be compromised. Thus, belief in the effectiveness of a treatment — even a placebo — can set off real biological responses via this predictive shortcut.

Still, the ethical use of placebos remains a challenge. In cases like depression, where placebo responses can be significant but inconsistent, relying solely on them may pose risks. For example, if a patient experiences only a temporary lift but is still at risk of suicide, and a physician failed to offer standard treatment like SSRIs, legal and ethical consequences may follow. For this reason, placebos are rarely used in isolation for critical conditions, despite their potential.

Placebo and Psychedelics

A 2020 study[3] explored placebo effects in a psychedelic context. Thirty-three students were told they were taking a psilocybin-like substance in a group setting filled with art, music, and visual effects. In reality, they were given a **placebo**, while confederates acted out mild psychedelic behaviors to enhance expectation.

Despite the lack of active drug, **61% of participants reported some effect** — from visual distortions ("the paintings moved") to sensations of heaviness or waves of altered perception. Some even experienced "come downs." This suggests that **set and setting**, combined with belief, can produce effects comparable in intensity to **moderate or high doses of psychedelics**.

References

- ↑ Bannuru RR, et al. *Effectiveness and Implications of Alternative Placebo Treatments*. Ann Intern Med. 2015;163(5):365–372. doi: https://doi.org/10.7326/m15-0623

- ↑ Rheims S, et al. *Greater Response to Placebo in Children Than in Adults*. PLoS Med. 2008;5(8):e166. doi: https://doi.org/10.1371/journal.pmed.0050166

- ↑ Tripping on Nothing: Placebo Psychedelics and Contextual Factors*. Psychopharmacology (Berl). 2020 May;237(5):1371–1382. doi: https://doi.org/10.1007/s00213-020-05464-5