Placebo: Difference between revisions

mNo edit summary |

mNo edit summary |

||

| Line 3: | Line 3: | ||

=== '''Why does the placebo effect exist?''' === | === '''Why does the placebo effect exist?''' === | ||

A key evolutionary | A key aspect of evolutionary success is the speed at which organisms respond to stimuli. Faster reactions increase survival rates, allowing those genes to persist in the species. This development is likened to an arms race, where genetic mutations evolve to enhance quick responses. Initially, simple chemical messengers were used, triggered by stimuli and resulting in responses, such as hormone release. | ||

Over time | Over time, evolution improved these systems, leading to the creation of neurons, which could send electrical signals at incredible speed. Neurons allowed organisms to react in near real-time. However, evolution pushed further, and the brain developed into a predictive machine. Instead of just reacting, organisms could anticipate where a stimulus would occur, allowing them to respond even before the threat arrived. This ability gave species with larger brains, including humans, a significant competitive advantage in survival. | ||

The placebo effect taps into this predictive mechanism. For the brain to make a quick prediction and act on it, the subconscious must believe the stimulus is real. If the stimulus enters conscious thought and is processed too long, valuable time is lost—time that could mean survival or death, such as when avoiding a predator. Evolution has kept this predictive mechanism in the subconscious, bypassing slower, conscious thought. | |||

Thus, the placebo effect is not a biophysiological function but an offshoot of the brain’s need for predictive behavior, connected to psychosomatic processes. | |||

In practice, the ethical use of placebos by doctors presents a dilemma. A placebo only works if the patient believes it will, raising questions about honesty in treatment. Imagine a doctor prescribing a placebo for a patient, who experiences some benefit but misses out on a more effective treatment. In cases like depression, placebos have shown notable effects, but they are not guaranteed to be effective enough in all situations. For example, a placebo might not prevent a severely depressed patient from committing suicide. | |||

If a doctor prescribes a placebo to a depressed patient and it proves insufficient, leading to a tragic outcome like suicide, the doctor could face serious legal consequences. In a court of law, a doctor might be found negligent for not prescribing more effective treatments, such as [[SSRI and psychedelics|SSRIs]], which are proven to reduce suicide risk. To avoid these risks, doctors often prioritize prescribing medications like SSRIs over placebos, even if a placebo might have some benefit. This approach ensures that they provide harm reduction and minimize liability, making the use of placebos less common in critical conditions like depression. | |||

=== Placebo and Psychedelics === | |||

In one study<ref>'''Tripping on nothing: placebo psychedelics and contextual factors'''. Psychopharmacology (Berl). 2020 May;237(5):1371-1382. doi: 10.1007/s00213-020-05464-5. Epub 2020 Mar 7. Accessed 12 Sep 2024 via: https://pubmed.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/32144438/ | |||

</ref> exploring the relationship between placebo and psychedelics T\thirty-three students completed a single-arm study ostensibly examining how a psychedelic drug affects creativity. The 4-h study took place in a group setting with music, paintings, coloured lights, and visual projections. Participants consumed a placebo that we described as a drug resembling psilocybin, which is found in psychedelic mushrooms. To boost expectations, confederates subtly acted out the stated effects of the drug and participants were led to believe that there was no placebo control group.The result of this study, showed '''t'''here was considerable individual variation in the placebo effects; many participants reported no changes while others showed effects with magnitudes typically associated with moderate or high doses of psilocybin. In addition, the majority (61%) of participants verbally reported some effect of the drug. Several stated that they saw the paintings on the walls "move" or "reshape" themselves, others felt "heavy… as if gravity [had] a stronger hold", and one had a "come down" before another "wave" hit her. | |||

'''Reference''' | |||

Revision as of 12:54, 12 September 2024

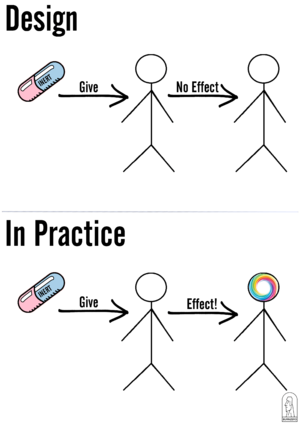

A placebo is a substance or treatment which is designed to have no therapeutic value. However, when administered to patients under the guise that it works, seemingly paradoxically an effect (termed the placebo effect) is shown (see Figure 1). This is thought to be caused, by priming via psychosomatic mechanisms.

Why does the placebo effect exist?

A key aspect of evolutionary success is the speed at which organisms respond to stimuli. Faster reactions increase survival rates, allowing those genes to persist in the species. This development is likened to an arms race, where genetic mutations evolve to enhance quick responses. Initially, simple chemical messengers were used, triggered by stimuli and resulting in responses, such as hormone release.

Over time, evolution improved these systems, leading to the creation of neurons, which could send electrical signals at incredible speed. Neurons allowed organisms to react in near real-time. However, evolution pushed further, and the brain developed into a predictive machine. Instead of just reacting, organisms could anticipate where a stimulus would occur, allowing them to respond even before the threat arrived. This ability gave species with larger brains, including humans, a significant competitive advantage in survival.

The placebo effect taps into this predictive mechanism. For the brain to make a quick prediction and act on it, the subconscious must believe the stimulus is real. If the stimulus enters conscious thought and is processed too long, valuable time is lost—time that could mean survival or death, such as when avoiding a predator. Evolution has kept this predictive mechanism in the subconscious, bypassing slower, conscious thought.

Thus, the placebo effect is not a biophysiological function but an offshoot of the brain’s need for predictive behavior, connected to psychosomatic processes.

In practice, the ethical use of placebos by doctors presents a dilemma. A placebo only works if the patient believes it will, raising questions about honesty in treatment. Imagine a doctor prescribing a placebo for a patient, who experiences some benefit but misses out on a more effective treatment. In cases like depression, placebos have shown notable effects, but they are not guaranteed to be effective enough in all situations. For example, a placebo might not prevent a severely depressed patient from committing suicide.

If a doctor prescribes a placebo to a depressed patient and it proves insufficient, leading to a tragic outcome like suicide, the doctor could face serious legal consequences. In a court of law, a doctor might be found negligent for not prescribing more effective treatments, such as SSRIs, which are proven to reduce suicide risk. To avoid these risks, doctors often prioritize prescribing medications like SSRIs over placebos, even if a placebo might have some benefit. This approach ensures that they provide harm reduction and minimize liability, making the use of placebos less common in critical conditions like depression.

Placebo and Psychedelics

In one study[1] exploring the relationship between placebo and psychedelics T\thirty-three students completed a single-arm study ostensibly examining how a psychedelic drug affects creativity. The 4-h study took place in a group setting with music, paintings, coloured lights, and visual projections. Participants consumed a placebo that we described as a drug resembling psilocybin, which is found in psychedelic mushrooms. To boost expectations, confederates subtly acted out the stated effects of the drug and participants were led to believe that there was no placebo control group.The result of this study, showed there was considerable individual variation in the placebo effects; many participants reported no changes while others showed effects with magnitudes typically associated with moderate or high doses of psilocybin. In addition, the majority (61%) of participants verbally reported some effect of the drug. Several stated that they saw the paintings on the walls "move" or "reshape" themselves, others felt "heavy… as if gravity [had] a stronger hold", and one had a "come down" before another "wave" hit her.

Reference

- ↑ Tripping on nothing: placebo psychedelics and contextual factors. Psychopharmacology (Berl). 2020 May;237(5):1371-1382. doi: 10.1007/s00213-020-05464-5. Epub 2020 Mar 7. Accessed 12 Sep 2024 via: https://pubmed.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/32144438/